By critic Jeon Bongho

Editors’ Note: The following article was originally run in 2005 and is a rare overview of the evolution of the gay community in Seoul. Gabriel Sylvian, the founder and torch-bearer of the Korean Gay Literature Project at Seoul National University, recommended it for all readers to get an idea of the LGBT life in the capital.

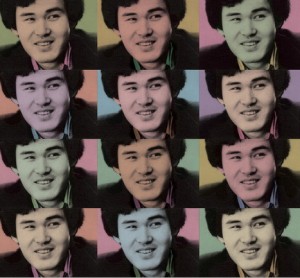

Gi Hyeong-do, the most memorable poet of the 1990s, died in 1989 of a heart attack, months before the publication of his debut, THE BLACK LEAF IN MY MOUTH. The place of his passing was the late night Pagoda Theater, which is known to the homosexual scene as a popular cruising area in Seoul. Twelve years after the poet died (2002), the theater, with its dangerous, mysterious, even fatal, and thus tempting atmosphere, also saw its end. Quietly, smothered, and disregarded, even belying the memory of the place.

most memorable poet of the 1990s, died in 1989 of a heart attack, months before the publication of his debut, THE BLACK LEAF IN MY MOUTH. The place of his passing was the late night Pagoda Theater, which is known to the homosexual scene as a popular cruising area in Seoul. Twelve years after the poet died (2002), the theater, with its dangerous, mysterious, even fatal, and thus tempting atmosphere, also saw its end. Quietly, smothered, and disregarded, even belying the memory of the place.

Gi’s work is still celebrated by readers and critics; the fact which is crucial in understanding his poetry (that he was gay) does not even appear in academic papers. Even though the thick and sticky mood which lies beneath all his work, obviously resembles the atmosphere of the men standing in front of the raining screen of the Pagoda Theater, the only description found for his work is grotesque realism. From the sexual identity of the author, all the homosexual metaphors and locations in his work, the hetero simply turns his head and ignores. How grotesque is that?

Neither in the TV news about the Keith Haring exhibition some two years ago, the description of Robert Mapplethorpe’s work, nor in the introduction to Mishima Yukio novels, appears the fact that they were gay. Their sexual identity was just wiped away.

exhibition some two years ago, the description of Robert Mapplethorpe’s work, nor in the introduction to Mishima Yukio novels, appears the fact that they were gay. Their sexual identity was just wiped away.

A queer mapping of Seoul in this kind of homophobe environment is no walk in the park. Centering in Itaewon and Chongro, the gay culture of Seoul grew like a culture of germs in a petri dish; hidden away and in quarantine. Like in the case of theater and poet, these spaces were not growing on general estimation, tolerance or even recognition. In a heterosexual world, there is not room for the homosexual, since it would not show on any map of Seoul.

Showing a hypocritical relationship to sex, a typical characteristic of Confucian culture, homosexual space was firmly restricted to the shadows of society. Naturally, in the beginnings of modern homosexuality in the 1960s, the only gatherings were at dark theaters, leaving room only for commercial sex. Also the gay-bars, frequented in the 70s and 80s, spread surrounding these theaters. These bars, seated in the hollow emptiness of an abandoned downtown, were just like their direct neighbors, nothing more than anonymous pick-up locations. It has not been long since I used to secretly ring the bell of a shut door, the only visible sign of a locality which saw its first customers late at midnight. Only ten years in the past, the gay-scene in Seoul was nothing more than this.

The Chongro area, where the Pagoda theater stood in the center of a gay-ghetto, was known ever since the Korean War as a market-place for sex. In 1968 the municipal government started the restoration of the area, and left a ripped neighborhood in which one by one, gay-bars started to be run. Even now, the neighborhood consists mostly of dirty and stinking back alleys, typical for the urban desert. The spatial identity influencing the thoughts and experiences of its occupants, it was impossible to verbalize a gay identity or develop a certain kinship, in bars that hid like guerrillas. These places rather promoted self-hatred and denial. The only thing left to do was the trade and dealing of sex. Treating each other as sexual objects, there was no chance for a human relationship. Expecting that a community can be built on the basis of pure sexual desire is nonsense. The gays of the day grew the astonishing ability to find their type even in the dimmest of lights. This distorted development nourished a negative awareness of space and the reduction of the other to a sex-object.

The dark and coarse Chongro area experienced a quake in the mid 90s; staring with the groups at Seoul National University in 1995 and other elite universities, the Korean Committee for Homosexual Human Rights was formed. For Korean society, which believed that homosexuality could and  did not exist, this collective coming-out was a shock. Especially, those who had kept their sexuality in the closet were influenced directly by these coming-outs. Stigmatized as mentally ill and hence denied, they were provided with a momentum to seriously reconsider their sexual identity. Formerly lacking a proper language to verbalize their sexuality, the coming-out of the social elite was giving them a persuasive way of expression.

did not exist, this collective coming-out was a shock. Especially, those who had kept their sexuality in the closet were influenced directly by these coming-outs. Stigmatized as mentally ill and hence denied, they were provided with a momentum to seriously reconsider their sexual identity. Formerly lacking a proper language to verbalize their sexuality, the coming-out of the social elite was giving them a persuasive way of expression.

At this time the Internet evolved and many were now able to expose and share their homosexual identity, to observe and participate in the articulation. The Internet expanded its influence, providing new information and language, also offering peers to share these with. Those exploring their new identity did not need to linger in the dark and dirty, backdoor-urban gay space anymore. It became possible to meet numerous gays without leaving the security and comfort of home, instead of risking a debut, coming out to questionable establishments, dark, worn, dirty and strange. The gay space, formerly being a child of the night, expanded to the hours in the sun, since the Web does not lay any restrictions on the user, when to use it. Most of all, the cyber gay space allowed homosexuals to grow free of the self-destruction and humiliation they had to feel occupying the dark and sticky bars. The Internet brought along a lot of improvements, but every medal has two sides; we will refer to this other side later on.

The start of the homosexual human rights movement was a great momentum for the progress of gay culture in Korea. The average age of coming-out dropped significantly and the age-span of new gays has never been wider. In this situation, the old-fashioned center gradually made place for a new Mecca of gay culture: Itaewon. The Spartacus, a full-scale dance club, wiped out the small bars in Chongro and became the magnet for young, hip gays. Every weekend they would come to a clean and bright, westernized atmosphere, experiencing a certain degree of freedom. Whereas the old bars were places of sticky glances through blurred liquor glasses, Itaewon had the joyful and modern flair only a dance-club can mediate. The new generation of internet gays found their offline space in Itaewon. Chongro was too small to stand hold to the new demand and also too old-fashioned to catch their taste. Beginning its triumph in the mid 1990s, Itaewon has established a new order in the queer world of Seoul: If you are young, hip and under 40, come to Itaewon. If not, go to Chongro, where the old boys are.

One of the most significant differences between Itaewon and Chongro is the openness of space. The area with all the bars and clubs, known as Homo Hill, is an exposed space, where young men greet each other on the street, giggling, hugging and exchanging nips; simply being so gay. In the old days and old places as you became complete strangers on leaving  the bar, this was a thing not imaginable. The establishments seem to fight for their existence by demonstratively flagging the rainbow colors and the hippest gay-club SPOT does not only draw gays but also heteros into his ban. The reason why Itaewon could become such an open gay town depends mostly on the geographic characteristic of the location. This place has always been an area for emigrates, nor accommodating the US military base and functioning as shopping area in the daytime and as amusement mile at night. In many Korean minds this place always had the exotic flair of pseudo-overseas, which is probably the major reason for the openness with which the gay community could establish itself in the neighborhood. Whereas Chongro was built on the ruins of brothels, Itaewon was shielded as an amusement center for foreigners. Considering that occupied space always reflects social perception to some degree, the local characters of the two gay centers of Seoul show just how primitive the understanding of gay-culture in Korea is.

the bar, this was a thing not imaginable. The establishments seem to fight for their existence by demonstratively flagging the rainbow colors and the hippest gay-club SPOT does not only draw gays but also heteros into his ban. The reason why Itaewon could become such an open gay town depends mostly on the geographic characteristic of the location. This place has always been an area for emigrates, nor accommodating the US military base and functioning as shopping area in the daytime and as amusement mile at night. In many Korean minds this place always had the exotic flair of pseudo-overseas, which is probably the major reason for the openness with which the gay community could establish itself in the neighborhood. Whereas Chongro was built on the ruins of brothels, Itaewon was shielded as an amusement center for foreigners. Considering that occupied space always reflects social perception to some degree, the local characters of the two gay centers of Seoul show just how primitive the understanding of gay-culture in Korea is.

Itaewon is much more exposed and open compared to Chongro. Nonetheless, just like the old center, it still seems to lack the capacities to visualize and stock experience. This is the negative side of the developing Internet. Having found their shelter in cyber space, the meaning and demand for a real place out here has drastically shrunk. Finding a place is no longer a goal in itself, but became a secondary tool, prolonging the virtual meeting in cyberspace. Many homosexuals entered the Itaewon era, still haunted by the negative image of their first OUT in Chongro, fearing and avoiding the exit into a gay-ghetto. Most of their stories and come-togethers rely on the internet, leaving only loud and bragging homosexuals exaggerating their gayness in a hollow show. Considering that a community establishes itself on the base of locality, Korea’s gay community does exist virtually in cyber-space; in the real world it is still missing.

Seoul has experienced the most vivid and dynamic modernization. But even so, the economic development always has been pushing culture to the back rows. In Seoul, where cultural capacity and flexibility seem to be lacking, it is hard to expect acceptance of a minority’s otherness. Especially the traditional esteem of the family, based on the principles of Confucianism, stigmatizes homosexual identity as immoral and antisocial. Thus, it is hard to call queer space an acknowledged part of the society. Social change of shifting the main focus from family to individual, the new attitude of a new generation of gays, and the restless effort to articulate sex as an issue, will hopefully contribute to social acceptance, giving the gay-ghetto a social name. Till then, we will have to follow the example of Gi Hyeong-do and seek, feel, agonize with, and sing of the queer space. This little exercise here (queer mapping) starts right there: by jumping into the OUT.

(* blog text modified slightly from original to account for grammatical errors)

“Seoul Until Now” Charlottenborg Udstillingsbygning, Copenhagen, 2005 (www.charlottenborg.com)