By Michael Foster

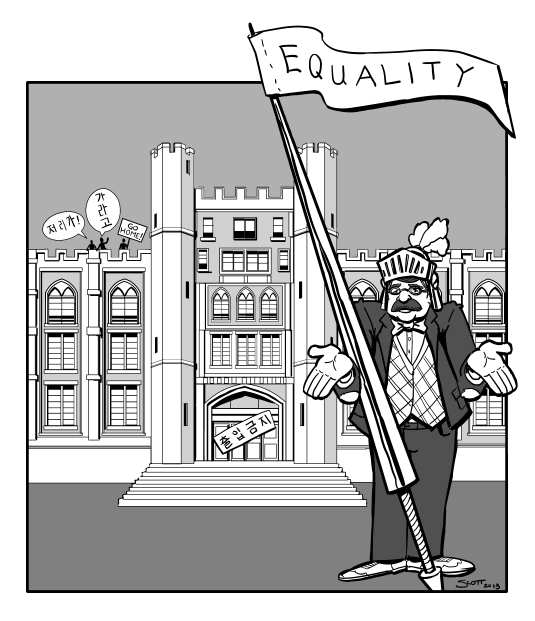

In January 2013, the Chronicle of Higher Education ran a story about foreign academics facing difficulties working in South Korean universities. My experiences at Korea University bookended the piece.

Unfortunately, the article's focus was on the least interesting and less important parts of my story.

I met and married my wife in 2009, after first meeting her in the United Kingdom where I was working on a research project. Since my wife, a South Korean, hesitated to leave her country, we decided to stay for a few years, especially in light of the push Korean universities were making to internationalize themselves. In January 2010, I was offered a tenure-track professorship in medieval English literature at Korea University in Seoul. Having a Korean wife and an open mind, I accepted. My subsequent experiences fomented skepticism in the ability of the university and the country to allow internationally recognized academics to prosper in South Korea.

The doubts came quickly. Shortly after being hired, I was warned by then head of department and feminist scholar Ms. Y that they had experienced problems with the last foreigner so I should make sure to behave. He, apparently, was not offered a contract renewal after his initial three years, although he was promised tenure after leaving a tenured position at the University of California, Santa Cruz. While the warning was dressed up as friendly advice, the reality was clear: I was different and would be treated thus.

At first, I accepted this. After all, I was given a housing bonus that Korean faculty were not, which gave me an opportunity to live in a nice apartment in Yeouido, my favorite part of Seoul. And since I could not speak Korean, it made sense to me that I would be treated differently from an administrative standpoint.

Quickly, however, cases of clear and arbitrary discrimination made me question whether the two-caste university system was tolerable, and the gradual escalation of pressure made me devise an exit strategy from the university and country within a year, which I planned to execute after fulfilling my three-year contractual obligation to teach at the university. I did not intend to pull a runner.

Except for attending conferences, I was not allowed to leave the country--not even for a few days. When I asked to leave to attend my grandfather's funeral in December of 2010, the request was denied. In the same month, a Korean colleague who was hired six months after me was given permission to leave the country for two and a half months. Ms. Y said that the faculty did not appreciate my asking to go, and that it made them question my devotion to Korea and Korea University.

In November 2011, things quickly worsened when another colleague, Ms. L, a Korean-American professor of English linguistics in my department, asked my assistant, A-yeong Seok, to forward all emails that I had ever sent to her. The reason for this was never clear to me, but when my assistant refused she became a "wangta" or outcast, and would resign and abandon her academic career within a year. This is tragic; A-yeong was a brilliant and promising student.

In March 2012, a department assistant used the head of department's stamp without his approval. The head of department, Mr. K, flew into a rage over this and requested that I be disciplined for the assistant's behavior. This guilt-by-association way of thinking makes little sense to me, but its presence in a Korean professor's mind still disturbs me--it is far too reminiscent of the generational imprisonment of North Korea, and suggests that the two countries are ideologically more similar than anyone outside the peninsula recognizes, in terms of how they understand guilt, individuality, and human rights.

In March 2012, a department assistant used the head of department's stamp without his approval. The head of department, Mr. K, flew into a rage over this and requested that I be disciplined for the assistant's behavior. This guilt-by-association way of thinking makes little sense to me, but its presence in a Korean professor's mind still disturbs me--it is far too reminiscent of the generational imprisonment of North Korea, and suggests that the two countries are ideologically more similar than anyone outside the peninsula recognizes, in terms of how they understand guilt, individuality, and human rights.

Things devolved quickly. Mr. K began sending threatening emails to me, ordering me to go to his office to be disciplined and demanding to know if I was in Korea or not—a question often asked of me. A typical example:

Now, as a department chair, I officially summon you to visit my office. You should come to my office on Monday or sometime next week to address your and our concerns. On my record, you are in Korea. So I believe there is no reason for you to visit my office soon. By the way, are you out of town or out of the country?

I requested your phone number. Please inform me of your phone number.

Once, he called me "pyeonshin gaeseki" ("retarded son of a bitch") over the phone--I have an mp3 of that, which I've kept in case anyone needs a copy. He also yelled at, threatened, and harassed A-yeong until she quit her position.

I emailed the Dean of the College and President of KU to report Mr. K’s increasingly bizarre and antagonistic behavior, and neither responded to my pleas for assistance. Instead, one of them (I do not know who) forwarded my emails to Ms. K.

Shortly afterwards, KU stopped paying me and refused to acknowledge my letter of resignation, which I submitted at the end of November. My letter was quite short:

To the Faculty and President of Korea University,

I, Michael Ryan Foster, officially resign from my position at Korea University effective immediately as of today's date, November 21, 2012. I officially withdraw from my position as Assistant Professor in the Department of English Studies within the College of Liberal Arts at Korea University.

In accordance with Articles 34, 42, and 45 of the Labor Standards Act of South Korea, I hereby request full payment of my pension and all outstanding wages owed to me by Korea University.

At the moment, the university owes me about 50,000,000 won (about $46,000). As long as my resignation is not acknowledged, I will be unable to receive the money in my Korean pension account. When I contacted the Labor Board in December and again in January 2013, they told me there's nothing they can do: Korean law allows employers to retain employees and not pay them. I also contacted two lawyers; one said I could sue and would probably not see any money for at least 3-4 years; another said it wasn’t worth the time, and that I was actually treated quite well relative to how most Koreans are treated. He also said this was unsurprising from “Minjok Kodae” (a reference to KU being of, by and for the nation).

The moral of this story is clear and unfortunately largely missing from David McNeill's piece: South Korea is simply not ready to provide an environment that internationally acclaimed faculty (who have options in other countries) can tolerate. I am not the first nor will I be the last to experience this; at Seoul National University, Andrea Pearson, an acclaimed art historian from the U.S., abandoned her position after three months upon discovering many promises made to her were empty. At KAIST, Steven Jordan,a finance professor, was dismissed following a series of questionable accusations. He is currently suing the school for allegedly unfair dismissal, demanding compensation for breach of contract and damage to his reputation.

At my own Korea University, two professors before me were driven out of the English department (both remain mum about their experiences due to legal proceedings). One was a Korean with a degree from the University of Chicago who I hear is now on the tenure track in America. His story demonstrates that this is not racial or nationalist discrimination. There are numerous cases of Korean professors committing suicide, resigning, or flocking to English-speaking countries to pursue their careers abroad. Korea's brain drain is all but guaranteed for as long as these shenanigans persist.

As for me—I left South Korea in May to receive some medical treatment in America, and I’m still technically a professor at Korea University. I get mass emails from administration all the time. I have asked about my resignation, and was told they cannot process it until I pay them 300,000 won to compensate them for a mistaken payment they gave me over a year ago, although they also owe me 300,000 won for another payment that was never released (on top of the months of owed back pay). I have emailed them multiple times about this, and received no response.

My books and things are still in my office—you can check it out at Seokwan 702 (but don’t knock—I won’t be there to answer). As much as I would love to reclaim a decade of primary materials on medieval manuscripts, paleography, medieval Latin, and European history, part of me thinks Korea University should keep the materials. With any luck, a curious Korean historian two centuries from now can find out where those books came from, and rediscover my curious tale.

I was quite sick when I left so it was difficult to think of much besides my own physical health. But after recovering and seeing the KU situation regress into a less and less professional mess, I realized that enough was definitely enough. I had been warned when receiving this job that Korea University was one of the most insular and jingoistic of the universities in Korea, and that I was facing an uphill battle. But I like challenges. Eventually, however, you have to give up tilting at windmills.

The opinions here do not necessarily reflect those of 3WM.

Cartoon By Lee Scott; photos by R.M. Adamson.

______________________________________

Michael Foster received his Ph.D. in medieval literature in 2009 after studying in America, the U.K., and Finland; his research has been published by Oxford University Press, Penn State University Press, and several other internationally recognized academic publishers. After his experiences in South Korea, he has left the country and now lives in New York City.