By Gabriel Sylvian with Iwazaru

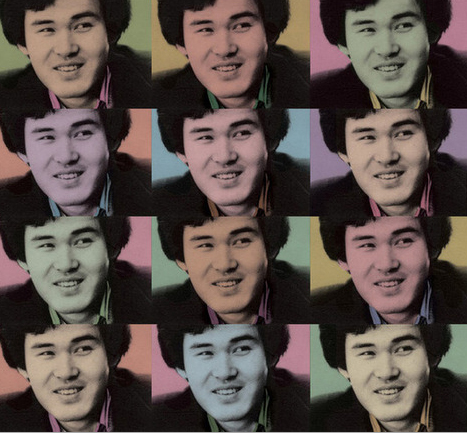

Gi Hyeong-do (1960-1989) is one of the most highly recognized names in modern Korean poetry. His poems are a staple in Korean literature textbooks, and the posthumously published volume of his poems The Black Leaf in My Mouth has gone through multiple printings in the two decades since his untimely death.

Gi Hyeong-do (1960-1989) is one of the most highly recognized names in modern Korean poetry. His poems are a staple in Korean literature textbooks, and the posthumously published volume of his poems The Black Leaf in My Mouth has gone through multiple printings in the two decades since his untimely death.

While growing up in a shanty town west of Seoul in Incheon, Gi’s family fell into poverty after his father fell ill with cerebral palsy. Gi was nine years old. Always a top student at school, his awards for outstanding performance filled up a ramyeon box. Gi began writing poetry in junior high school after one of his older sisters died suddenly in an accident.

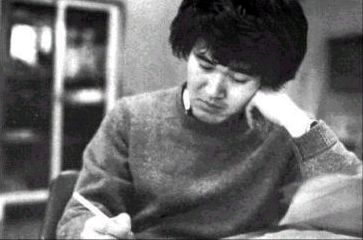

As a college student in the Political Science department at Yonsei University, Gi continued to publish occasional poems and short stories. While suffering family and personal illness, and under pressure to be “the man” at home following his father’s collapse, Gi’s refuge was literary art and music.

He is remembered for his eagerness to talk about poetry with anyone, his strong baritone voice, and passion for karaoke. He is also remembered as having had a cheery personality to the world which made his dark poetry shocking to those who knew him. After graduation, he worked as a reporter for the Joongang Ilbo, first as a reporter for the newspaper’s much-coveted political section, but later in the cultural section by his own preference.

His corpse was found in the early hours of a spring morning at the Pagoda Theater, a gay sex venue in Jongro 3-ga central Seoul, dead of a heart attack at the age of 29. The circumstances of Gi’s death and his homosexuality have been systematically covered up and/or ignored by mainstream scholars trying to “protect” his image from any association with sexual minorities.

Gi’s poems are most noted for themes of death, loneliness and despair, but he also wrote poems about love and desire struggling to survive in webs of overwhelming psychological oppression. Although his poems express same-sex themes both explicitly and in veiled language, and although the oppressive existence of the 1980s urban homosexual is the reference point from which he railed at the arbitrary “laws” (discrimination) of his society, there has never been an academic paper or criticism in Korea, since 1989, discussing this important aspect of his life and art, as though (like the Korean Lesbian-Gay-Bisexual-Transgender (LGBT) community today) they did not exist.

Similarly, the scene of Gi’s untimely death is either described generically by Korean critics as a “late-night theater” or with repulsion as a “blood-curdling” place. Even today, mainstream Korean intellectuals, when referring to the circumstances of Gi’s death using the euphemistic term “p’ungmun,” or “rumor,” imply that Korea’s same-sex culture is a disgusting thing, rather than identifying the disgusting oppressive conditions that society imposes on gay men. Ironically, this social contradiction is precisely what Gi spent his short adult life suffering, and in poetic works like “Put Badly” that bear the seeds of an emerging activism, harshly condemning.

Following its overturn of decades of homophobic discourses surrounding the early modern writer Yi Gwang-su, The Korean Gay Literature Project at Seoul National University is now breaking the silence about Gi’s homosexuality by addressing the same-sex themes in Gi’s poetry as same-sex themes, and by “internationalizing” Gi, foremost as a good Korean poet but also as a good same-sex poet—via exposing his work to the world in English translation. After the outside world gains an appreciation for Gi, the poet’s large readership at home perhaps will then be able to “see” Gi for who and what he was, and appreciate his voice as an important element for GLBT history.

___________________________________________________________________

Grass

I have an appendix but

I don’t like eating grass

I am

a poor excuse for an animal

I live as a spirit pitched to and fro

roaming clouds streaming with sleep

baring the veins on my wrists

a long sorrow

When I take my body, empty, and stand before you

your waving gestures

are signals so green it makes me sad

Ah,

but the love you retched up while guarding the night!

Was that your beautiful soul

that sustained the darkness, erected the blades?

Now I shall take root!

Better to be grass, having to cry smiles

Let’s suffer life’s afflictions

Let’s bind our feet together and sob

When the winds blow on clear days

and lightly caress my bruised sides

my song, which delves into my heart, springs up, and becomes you

will form groups, crisp and fresh,

and float in the air.

Front of the Bar

That day it was blindly reeling winter

We were there with all the others

Everything was my fault

Our nearness comforted me

I’m going to forget that bar

I’m going to escape the memory of it

The guys were downing booze with all their might

The looks I gave were spilling out like straw

My heart couldn’t let you hear it cry

The same person doesn’t exist now

All memories lost their stations

I sobbed there at the bar

That blindly drunken winter

We were there with all the others

The men clinched their remaining strength and reeled

My lips were ugly

It was all my mistake

But I sobbed there, next to the pile of coats

No jeers could hoist my heavy heart

I’m going to forget that bar

The same person doesn’t exist now

There, in that cramped and narrow place, I lost my love

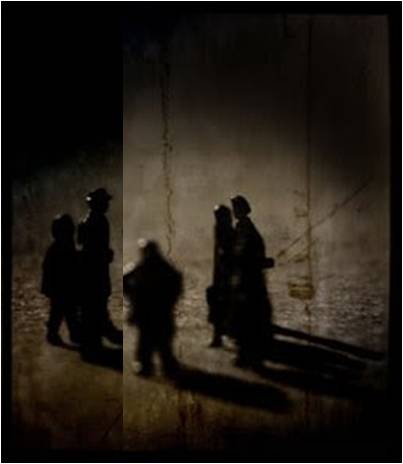

Put Badly

A few shadows hung around in the dark

Some stayed by the pitch-black wall

Sensing trouble, vehicles killed their lights

In an instant, each building bolted its door

and waited in fear. An explosion of kerosene fumes

a thin, slinky sound of dragging metal

black leaves leered as they tumbled by

hands and feet moved quickly

the flicker of cigarettes, somebody who walked into the alley

uttered a cry of shock

Those guys, why do they gather in the dark every night?

Where do the desires of those young men go?

Why are human pleasures all the same?

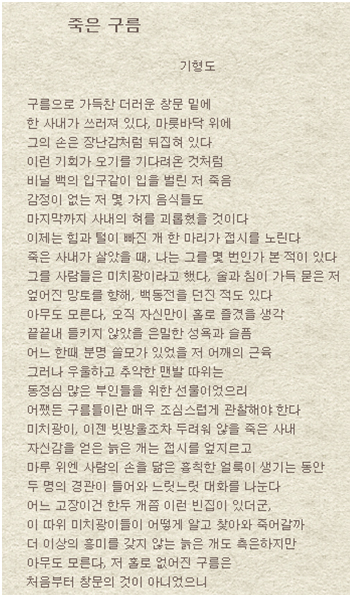

Dead Cloud

Below the dirty window filled with clouds,

a man has collapsed,

his hand upturned on the floor like a toy

He’d waited for this chance, it seems,

for death gaping like the mouth of a plastic bag

those unfeeling foods tormenting his hunger until the very end

Now a dog stares at his dish, having lost its strength, its fur,

I saw the dead man several times while he was alive,

People called him crazy, threw silver coins

at his outspread coat blotched with wine and spit

No one knew his private thoughts,

the sexual desires and sorrows he hid to the last,

his shoulder muscles clearly once had a function

His pitiful, vile bare feet

were gifts for tender-hearted women

but no matter, clouds must be observed with great caution

Now this fool, this dead man,even the raindrops do not fear him

The old dog, becoming bolder, knocks over the dish

and while villainous stains spread like human hands across the floor

two police officers enter and converse idly,

“All towns have one or two of these empty houses

A crazy fool like this–how did he know to come here and die?”

The old dog, having lost interest, seems sad

But no one knows, for the cloud that vanished alone

had no part in the window from the start.

__________________________________________________________

Gabriel Sylvian is the founder and torch-bearer of the Korean Gay Literature Project at Seoul National University where he conducts a study group called R/Z회. He was at Yonsei University (85-6) at the age of 19—the same year Gi graduated—and has been familiar with the Jongro underground same-sex scene for more than 25 years.

He earned an M.A. in Oriental Languages at UC Berkeley and came back to Korea in 2004 as a Fulbright scholar at SNU expressly charged by the Korean government with the task of doing the Project (“using literature as a tool for social change in respect to sexual minorities”). He has since earned an M.A. in Modern Korean Literature and is working on his doctorate.

He has translated Gi’s Complete Poems and is now seeking a publisher.

He can be contacted at rkngel@naver.com