By Gabriel Sylvian

Self-creation, experimentation, rejection of tradition and popular mass opinions and behaviors, even humanist philosophical positions—such make an individualist. Korean writer Bae Su-ah has stood for 20 years as an unrepentant individualist in a deeply nationalist and groupist literary establishment, in which conservative social systems–governmental, educational, familial, marital–support and suffuse what writers think and produce. Bae shuns conformity, is a self-learner, openly professes a hatred of groups, and rarely installs Korea and Korean culture as an explicit feature in her novels, preferring imaginary and foreign lands and languages as experienced and registered by her self. Her writing is quirky and hybrid, and it is exciting that her work, after 20 years of writing for Korean readers, is beginning to reach foreign readers through translation.

Early critics called her “escapist,” but that’s just on the surface. While her head seems to be “in the clouds,” her feet are planted solidly “on the ground.” With a keen eye, Bae observes life, humanity, and society and casts the problems deftly in self-contained quasi-fantasy worlds. Für Elise, Amelie’s Pastel Drawings, Indian Red Roof, Princess Anna, Hill of The Cold Star are some of the “exotic,” fairy tale-like titles by which readers first came to know Bae Suah in the early 1990s. But at the heart of her stories, we meet women struggling to survive in shattered families, coping with chauvinistic boyfriends, who relieve stress with food and daydreaming, who suffer from low self-esteem. Many of these life problems are rooted in the systems that she rejects.

Bae writes because she cares. But the tension between her individuality/aloofness from social and political structures, and her deep concern for individuality and self-respect amidst these structures has, perhaps not unsurprisingly, gotten her into hot water (not to say that, as a staunch individualist, it bothers her). In the year 2000, her essay “Two Packs of Marlboros and Three Bottles of Heineken” appearing in the Hangyeoreh 21, drew the ire of some readers. Appearing after the election, the essay served up a wry portrait of a disaffected 30-something voter:

I’ve never boasted of my political apathy. I know voting’s a good thing if you can do it. Then why is it, for some reason, whenever voting day rolls around, a friend comes to visit, or I end up going to see a good movie, or I have to give the dog a bath? Well, I thought this time I should vote, no matter what.

First, I looked at a list of candidates black-listed by a citizen’s group to see if anyone was running in my area. Fortunately, there was no one. One of the reasons for voting, gone. I checked to see if there were any new candidates in their 30s. Unfortunately, none. Another reason for my having to vote, gone. Finally, I looked to see if there were any good-looking people like Kennedy, but of course, there weren’t. . . . The smiling candidates looked greasy, the old ones looked scary. These people, if any of them were elected (it’s the same now, of course) had nothing in common with me. I figured I’d been worrying about nothing. On election day, I got up at dawn, went to my job at the company, and worked all day. [excerpt]

The essay, read without a sense of irony, sparked a small wave of public fury. A professor of media studies wrote that the essay “left him out of breath,” adding that such “irresponsibility” was indeed “rare for a writer.” Another commenter lambasted the Hangyeoreh for running a meaningless personal anecdote in its “public forum” column, saying that it left him feeling “most unpleasant”. But other readers, seeing beneath the façade of Bae’s aloofness, caught on that it was a political statement, or rather a “parody,” a sharp indictment of a rotten  political system that invites voter apathy. One enlightened commenter, begging the public to read the essay as a political critique rather than at face value, assured readers, and rightly, that “[beneath the surface,] . . . there’s politicality hidden in Bae Su-ah.”

political system that invites voter apathy. One enlightened commenter, begging the public to read the essay as a political critique rather than at face value, assured readers, and rightly, that “[beneath the surface,] . . . there’s politicality hidden in Bae Su-ah.”

Because she has been, and remains, something of a controversial figure in her home country, and also because her work is now beginning to appear in English translation (read an extended excerpt here), I decided to interview Bae for The Three Wise Monkeys to discuss her views on literature, politics, and her creative work.

F: Korean literature in the 1990s was a kind of renaissance, a flowering of new voices, especially women’s and gay voices, after decades of Korean writers following the prescribed “duties” and “roles” assigned them by society under the dictatorial regimes of the 60s, 70s, and 80s. It was a heady time. Liberality in literature and politics was fresh, exciting …. You made your literary debut at the beginning of this radical break with the past. In an essay written in 2000 entitled “An Excuse for My Texts” you wrote “Literature didn’t exist…before the 1990s.” I take it that you meant this in both the chronological and “substantial” sense. … The characters in your short stories of the 1990s were developed around imaginative, “exotic” themes and images that were unlike anything seen before in Korean literature.

Well, let’s begin with the question: To what extent do you see your work as a reaction to 80s literature?

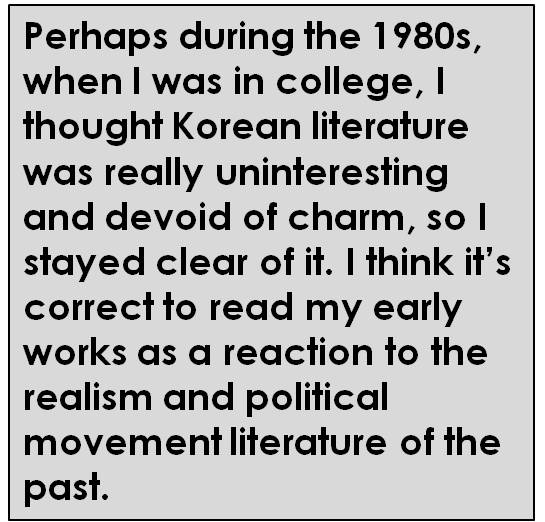

Bae: What you say is a reasonable assumption from the standpoint of a critic. That was what it was like in 1993 when I debuted as a writer. It’s true that for me no literature existed before the 1990s. Before writing my first short story, I didn’t read literature avidly. Probably more accurately, I didn’t like Korean literature. Before the 90s, I read world literary classics, and novels translated into Korean. That was all. At first, I was taken aback at criticisms saying that my literature was a resistance to the 80s literature. That’s because I didn’t know much about 80s writing and so had no intention of contesting or resisting it. Perhaps during the 1980s, when I was in college, I thought Korean literature was really uninteresting and devoid of charm, so I stayed clear of it. I think it’s correct to read my early works as a reaction to the realism and political movement literature of the past. But it wasn’t contrived that way by my individual will. The trend of the time demanded personal individualism. It just so happens that it was the time when I finished my first short story and sent it to a magazine.

F: [That was a haunting short story called “A Dark Room in 1988”.] … In your first full-length novel in 1995, Rhapsody in Blue, you “rhapsodically” wrote about failed family and romantic relationships from the perspective of an unstable teenage girl who is passive, begs sympathy from others, a girl “trying to dance on a rope”. The problems of young girls at home, school, and in romantic relationships, are a staple of your early work. While your works express deep sympathy for girls and women alienated from all sorts of systems (marriage, family, school), at the same time, they’re often very critical of male power and the “male mind.” In this sense, your literature has always possessed a strong feminist consciousness, yes?

Also, did your personal experiences and those of your friends influence your literary themes and style?

Bae: I and other women writers from my time period often liked to write characters based in the vantage points of “women” in Korea. Some female critics have read my works from that angle.

In my early works, I enjoyed choosing “unstable women” as characters: a young girl who leaves her parents and is placed in foster care, a daughter unloved by her family, a young woman without a job, a woman jilted by her lover, a woman who’s just ended an unhappy marriage but who has no alternatives available to her, a woman with no knowledge about her future, etcetera. I was very intereste d in these sorts of lives. They stimulated my emotions and interest as a writer. I liked stories about these women. But does my being a female writer, and my preference for characters who are social victims, make me a feminist? I don’t think so. Instability in life is something I dealt with all throughout my formative and adolescent years, and I was compelled to write about it. That’s all.

d in these sorts of lives. They stimulated my emotions and interest as a writer. I liked stories about these women. But does my being a female writer, and my preference for characters who are social victims, make me a feminist? I don’t think so. Instability in life is something I dealt with all throughout my formative and adolescent years, and I was compelled to write about it. That’s all.

The characters in my recent novels differ a little from those of my early works. They’re still women, but my recent characters often are on a voyage, and experience linguistic confusion in foreign countries and have difficulty in articulating their thoughts. Expressed critically, these works can be said to cross back and forth between the boundaries of language and existence. That perspective, however, is strictly limited to the subject matter, and is rather abstract in its interpretation. What I wish to do is not cross boundaries but to be wholly oblivious to them. Why I like dealing with travelers in my stories is because traveling is a good way for me to experience impacts from the world. My characters are unmarried and in many cases, live unstable economic lives as freelancers. But they feel they’re free and are always involved in love affairs. There’s no call for them to “decide” to cross a boundary. They don’t strive to change the world and they don’t believe that they can change other people’s minds, no feeling they must cross a boundary nor any desire to do so. While they are, in fact, surrounded by boundaries, they’re not conscious of them, strangely enough. Under some conditions, they don’t have any boundaries. I’m interested in these people, these sorts of lives. But most criticisms interpret my stories as struggles or the will to cross boundaries. I’m guessing that the above is one of the reasons why my early stories were read as feminist.

F: Well then, what about your topicalization of social problems? More recent works from the 2000s deal with broader social issues like poverty (Sunday at the Sukiyaki Restaurant), gender (The Essayist’s Desk), and the educational system (The Self-Learner). In your essay “An Excuse for My Texts,” mentioned earlier, you also wrote, “I fear being in a position where I can influence other people in even the smallest way, or being in a power relationship.” Do you still feel that fear? What occasioned your coming to deal with more politicized themes (if you agree with that premise)?

Bae: Sunday at the Sukiyaki Restaurant, The Essayist’s Desk, and The Self-Learner, are comparatively less representative of my style. As you point out, those can be read as my most strongly political novels. I should explain. For example, I may (as is my habit) write about the inescapable “instability of life,” or perform a solitary serenade of sadness, but behind it all, forever looms the portrait of the dictator. That portrait looms behind the public buses running down the streets. To me, such a scene belongs to the grotesque. Politics, society, customs, human relations- from the standpoint of literature, these are all grotesque. It’s a different language from literature.

What I fear is the public power to instantaneously substitute the grotesqueness described by the author into political language. Because the inescapable instability is the dictator. That’s what my books are about. Of course, it’s the reader’s right to interpret the book as he or she likes. And that’s what I fear. I don’t want to be like a philosophy teacher just because I write books. I don’t know what good and evil are, neither do I really know what the concepts of “the human,” or “ethics,” or “the future,” or “happiness” are, neither do I believe in them. I don’t know anything. As a writer, I can’t say anything about human problems with certainty. It’s closer to say I don’t want to know them with any certainty. I don’t know anything. I don’t want to know anything. Because knowing, to me, is tedious. I like to observe life without intervening, to make assumptions, to imagine, and to fictionalize.

F: Political writing means “taking on the mantle” of so many burdens extraneous to the process of pure creative writing. Looking at your works chronologically, my subjective impression was that your more politicized work in the 2000s represented a kind of Ubergang into a more socially committed phase of writing, compared to the 1990s. I find an enormous positivity in the moments of fierce resistance in Bae Su-ah’s literature. But the “fearful” aspect of your thought jibes squarely with your rejection of “systems” in your writing. It’s important, I think, that readers understand this point about your work.

Bae: I understand your concern. My response just now, of course, was as a writer. I meant that for my works, political problems do not carry greater importance than other themes. The novels you mentioned deal with social issues, it’s true. But they don’t say anything more about my literature than the other works. Of course, I can’t say that they’re not my works.

Feminism, poverty, and gender are problems that my characters possess. But at the same time, those issues are often appropriated into the framework of “general literary readings.” That’s something I caution against as a writer.

I’m not at all indifferent to social issues. The main reason I’m interested in social issues is because they ’re fertile ground for creative writing. Even if I call my literature a literature of my personal dreams or fantasy literature, I believe that these grew and took shape in the realities of the society in which I and my readers live. Social problems are caused by human beings, and human beings are the characters in my novels.

’re fertile ground for creative writing. Even if I call my literature a literature of my personal dreams or fantasy literature, I believe that these grew and took shape in the realities of the society in which I and my readers live. Social problems are caused by human beings, and human beings are the characters in my novels.

But the resolving of social problems, social justice, social reform, and so on, are different notions. They’re not my direct concern. Nor do I think they impact my literary creations. That’s because I don’t think political methods lead to the betterment of society. I don’t want to write novels describing reality just “as it is” like naturalistic writers. I enjoy observing people.

F: Thinking back to the 1990s, it’s really what set you apart from the Korean women writers who monopolized most of the critical spotlight. Here, I’m thinking of Shin Gyeong-suk, Gong Ji-yeong, and Gim In-suk, who were writing within and about family, marriage, labor conditions under the sponsorship of Changbi Publishers–the powerful “old-boys” from the dictatorial era. While producing much good work, they did not break radically from the 1980s. But Bae Su-ah always wrote “from without.” It’s what made you unique, and imbued your works with a sense of freedom so fresh and appealing at the time. As I recall, that freedom bothered senior critics (mostly university professors). They saw you, Baek Min-seok, Jang Jeong-il, and other highly individualist writers as bearers of anomie and panic, and called your literature a “literature of crisis.” They were adverse to the postmodern break from the past you represented. Your literature is highly unique and differs markedly from the style of other Korean writers, so your works have been loved by readers. Can you make any additional comment on why you think that is?

Bae: Well, your question contains a lot of pretexts…. it’s a truly difficult question. That my literature differs from other Korean authors, whether my works are loved by readers for that reason, I don’t really know about that.

You know German, so you’ll understand the concept of Eigensinn, which is the sole dynamic underlying my life and writing.

F: In English, “self-will”, “stubbornness.”

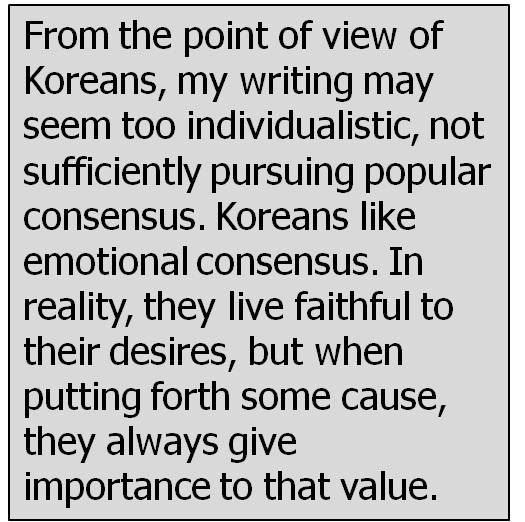

Bae: I think it may result from this. From the point of view of Koreans, my writing may seem too individualistic, not sufficiently pursuing popular consensus. Koreans like emotional consensus. In reality, they live faithful to their desires, but when putting forth some cause, they always give importance to that value. It’s the same in the literature. So, in the German-English dictionary, Eigensinn is rendered as “gojip” (고집). I think that’s an inappropriate translation. “Strong individuality” seems better.

F: From all that you’ve described, the title of your novel Self-Learner surely points toward something profound about you. What does the concept of “self-learning” mean to you?

Bae: I never learned anything in school. I didn’t pay attention during class, and was just absorbed in my imaginings. It was like that from kindergarten through university. Thus, all that I have inside me now is the result of self-study. Reading, thinking, experience, mistakes, they were all self-acquired.

F: Your choice to study German is also quite unusual for a Korean writer. …Speaking of German, in Self-Learner and in The Essayist’s Desk, you wrote about the difficulties of studying a foreign language, yet in the same year you published your Korean translation of Jakob Hein’s Mein erstes T-shirt. Hain criticizes the negative effects of education on students in the GDR during the 70s and 80s. It seems some parallel exists between Hain’s novel and your personal experience as a student in Korea. How did you come to translate the novel?

Bae: I’m embarrassed to confess it (laughs) but the selection of Hain’s book as my first novel to translate wasn’t so much its impression on me, as the book’s comparative simplicity for translation. I hadn’t been studying German that long and my abilities were still quite limited. It’s still hard. Somebody recommended the book to me, saying it was interesting. That’s how I came to read it. Germany was also once a divided country like Korea, and I thought the stories about being young in East Germany would be interesting for Korean readers.

F: How about your more recent translations of Bernhard’s Wittgensteins Neffe and Kafka’s Ein Traum?

Bae: Wittgensteins Neffe I translated at the request of the publisher. I was happy to do it because I like Bernhard’s writing. I read Ein Traum for the first time in Germany and really liked it, so I sent a proposal to Workshop Publishers and it fit perfectly with their Propositions Series.

F: Many think you moved to Germany. Did you?

Bae: Oh, I never moved to Germany. I live in Korea. My long sojourn in Germany was 11 months between 2001 and 2002. I went because I quit the company where I was working and wanted to become a full-time writer. I went to Germany and ended up, coincidentally, studying the language. I think this was one of the great fortunes of my life. Because I could become intimately acquainted with German literature. Of course I’ve gone back many times, but for just short stays of 2-3 weeks.

F: That’s a good segue into a question I’ve always wanted to ask you since reading your novel The Essayist’s Desk. Professor Im Ok-heui described the intentional gender ambiguity in Essayist as “queer.” Your novel Ivanna from 2002 also shared a similar gender ambiguity. Homosexuality appears as a theme or motif in your short stories Time in Gray, the Hyundae Munhak Prize-winning In the Direction of Marzahn, and A Letter from Yanggon. The straightforward and non-prejudicial manner in which you include themes of same-sex sexuality and gender fluidity marks another point in which you depart from other mainstream Korean writers. Can you say something about the background to Essayist? How did you come to write a “romance” (?) free of gender categories? And now, 10 years later, can you say if any connection exists between the title Ivanna and the Korean word for “gay,” ivan (iban)?

Bae: The Korean spelling of the title is Ibana (이바나), but the name in the original language is Ibanna/Ivanna. There was no special reason for choosing that name and there’s no connection to the Korean term ivan. I’ve never thought that the title might be interpreted that way. That’s quite clever.

Essayist was envisioned while I was in Germany. I think my novels are primarily love stories, though I don’t know how much my readers would agree with that. One day I was deeply inspired and fell in love. The person was my German teacher. It’s a common enough occurrence. We can easily fall in love with an excellent teacher. But as it happens, that German teacher wasn’t a man. But the novel describes their love very platonically. That’s why I think Essayist is half-success and half-failure. I lacked the courage to go forward, and my feelings were too much like those of a young girl in middle school.

But the situation wouldn’t have been much different even if that German teacher had been a male. And so the novel doesn’t have any same-sex code.

F: Your thoughts on gay rights? Support or no?

Bae: I don’t particularly “support” gay rights. That’s because it’s such a “no-brainer.” If one day I were to fall in love with a woman, I’d have no qualms, I would pursue it. If circumstances called for it, I’d tell all my friends. That wouldn’t be a problem for me at all. I think the response of my friends in that case would be based not so much in their values with respect to homosexuality but in their faith and trust in me. I just can’t understand why people make an issue out of others’ sexual orientation. Furthermore, I can’t understand why others worry about people problematizing their own sexual orientation. It’s the same for all modes of private life, not only sexual orientation. Just as there’s no reason for me to come forward and oppose another person’s love, there’s no reason for me to come forward and support it. I haven’t any right to do so. Private life is an individual’s “real” life; and “real” means “all alone.” I understand human rights (related to homosexuality) in the same context.

F: I asked only because you have topicalized same-sex attraction in your works, and because readers encountering those themes may be curious about your thoughts on the issue. For some of us, gay rights and building a political platform is an “in your face” business, but as you said earlier, this can constitute a different language from literature, especially pure literature. You want to be read as Bae Su-ah, not as a feminist, or queer supporter, etc. That marks you as an individualist. The Essayist’s Desk will be coming out in English translation soon. Isn’t that right?

Bae: Yes, it’s been translated into English. The translator Deborah Smith has completed it and negotiations are underway with publishers.

F: Which Korean or foreign writers do you enjoy reading?

Bae: My favorite author is [W.G.] Sebald. I love all his books. I truly love him. Currently I’m reading Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow. I like Pynchon’s other novels. I still can’t say whether I’ll like this one or not. I just started it. I also like J.M. Coetzee and Philip Roth. When I’m taking a break from work, I sometimes read Geoff Dyer’s essays. They’re interesting.

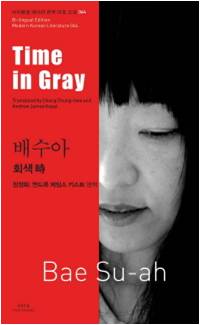

F: I’d like to ask you about the foreign language translations of your works, to date mostly in English. Your devoted fans are hoping for a Bae-boom. (laughs) Time in Gray has been translated, and, I believe, also your early short story Highway with Green Apples (with that disturbing pair of German kitchen scissors). Your early novel Cheolsu and The Essayist’s Desk– also forthcoming in English. Have you been satisfied with the results? Which of your works would you most like to see translated into English or another foreign language?

Bae: I haven’t read the translation of Cheolsu. I hope to read it when it comes out. I read Time in Gray, but my English ability isn’t strong enough to evaluate the translation. Speaking just from my feeling, I think there are no problems with it. I think when translating, the translator must be given a lot of freedom. The translation has to fit into the environment of the target language. When necessary, the expressions can be revised. I think translations that stick too closely to every Korean word and don’t move forward are not good translations. It’s something I’ve come to feel in the process of translating works myself.

When Amazon Crossings in the U.S. asked me to recommend some of my works for translation, I chose Cheolsu because it was on the Korean Literature Translation Institute’s list of recommended titles. I also recommended The Unknown Night and Day. I’d like to see it translated. Cheolsu has a pretty clear storyline. Personally, I like Northern Living Room and Low Hills of Seoul, but will they translate well into English? I’m also a little suspicious as to whether foreign readers would want to read Third World novels like those in Korea.

When Amazon Crossings in the U.S. asked me to recommend some of my works for translation, I chose Cheolsu because it was on the Korean Literature Translation Institute’s list of recommended titles. I also recommended The Unknown Night and Day. I’d like to see it translated. Cheolsu has a pretty clear storyline. Personally, I like Northern Living Room and Low Hills of Seoul, but will they translate well into English? I’m also a little suspicious as to whether foreign readers would want to read Third World novels like those in Korea.

F: Your works stand apart from those of your contemporaries in Korea for their postmodern quality, and should be of interest to foreign readers. Shin Gyeong-suk is a touching writer, and she had some success in the West with Please Take Care of Mom; but as mentioned, she and most other Korean writers are tied up with patriarchal and national “systems,” marriage, family, education, economic, and traditional motherhood. They write in the shadow of the portrait of the dictator. (laughs) Bae Su-ah, on the other hand, deconstructs and rejects these, creates her own unique literary worlds based in her individuality. Therein lay your great appeal, in my view, and I think other foreign readers will agree.

Bae: Well, I’ll say this: The place where I exist as a writer (not as a person) doesn’t “belong” anywhere. Literature can be seen as an act undertaken for social solidarity; but to me, literature is just “me alone.” And the more I write, the stronger that feeling grows.

F: Finally, what literary creations are you currently envisioning?

Bae: I just sent a collection of travel essays to my publisher. It’s called One Week with a Sleeping Man and is about my travels in Los Angeles. I never imagined my first travel essays would be about L.A. rather than Germany. I’ve often been asked to write some travel essays about Berlin. But I’ve never been able to finish them. I hope to finish them sometime next year…During the winter, I’ll be hard at work translating. Then in the spring, I’ll try my hand again at some love stories.

F: Thank you.

____________________________________________

(Translated by interviewer.)

Gabriel Sylvian is a researcher at Seoul National University.

Print This Post

Print This Post