Editor’s note: The writer of this piece requested anonymity due to the sensitivity of the subject. Any responses can be sent to 3wmseoul@gmail.com

The one common thing that all sexual minorities share in Korea is the difficulty to gain acceptance, no matter what they define themselves as. The topic itself is taboo, and never taken lightheartedly. Curious, I once brought up LGBT at the family dinner table to see how open-minded my parents were on the topic. I asked them about their opinion on gays and transgendered people. My dad chastised me.

The one common thing that all sexual minorities share in Korea is the difficulty to gain acceptance, no matter what they define themselves as. The topic itself is taboo, and never taken lightheartedly. Curious, I once brought up LGBT at the family dinner table to see how open-minded my parents were on the topic. I asked them about their opinion on gays and transgendered people. My dad chastised me.

“Why do you even want to talk about a subject like that? As if you’ve got nothing else to do. You could talk about those things later. So just concentrate on your studies and other work for now.”

Déjà vu. I had gotten that response before, when I once mentioned the matter of virginity and premarital sex. A disgusted face, a “Why do you want to talk about that?” and a reality check. This time, it was a bit more serious. I sensed that LGBT was a very sensitive topic and that it was the last thing my dad wanted to talk about. From looking into his eyes, I could also sense that he was afraid of me coming out of the closet or something. My mom shot him a look and said, “It’s okay. She just wants to talk about it. No harm. Isn’t that right?” She emphasized the “just” and “talk.” She didn’t want me to “get involved” in it, though she is willing to approach it as a subject of discussion and debate.

I asked them once again what they thought of gays. My dad denied their existence. “There’s no such thing,” he said. “It’s an abnormality that people made up.” I pointed out that there are a lot of studies that show homosexuality in other animals. I also talked about the spectrum of sexuality and that most people weren’t 100 percent straight or 100 percent gay; we all belonged in different places along the spectrum. My parents both shook their heads as they told me that those “studies” are nonsense manufactured by gays and their supporters. I clearly wasn’t making any progress.

I then switched the topic to transgendered people, something that I could relate to a bit more. My mother thought that they were amusing. She did not understand why transgenders, especially trans-women, loved to dress in such flamboyant ways and why the queers always wasted their time drinking and ranting in bars. She said that she would accept them once they begin functioning as “normal” people with decent jobs. I thought to myself that I would choose to drink my years away if I had to endure this talk for the rest of my life. My parents also obviously wanted to end this talk as soon as possible.

The conversation finished with a bang as I asked them the final, forbidden question: “What would you do if I came out of the closet or told you that I want to switch genders?” Panic filled their eyes. My father started fuming, again questioning the entire point of the conversation, telling me to stop even thinking about it. My mother hastily wrapped up the topic saying, “I wouldn’t like that. The world’s too harsh for LGBTs, and before that, there’s no such thing as being gay or transgendered. It’s all just personality problems. People just have their usual differences. Anyways, I know that you’re not gay, so I’m not worried.”

“I know that you’re not gay,” she concluded, as if she were convincing herself as well as me. My mother doesn’t know me as well as she thinks she does. Don’t worry, mom, your daughter’s not gay. She’s just a bit… queer.

Don’t get me wrong. I love my parents. They would support me in most other ways. They love me dearly. It’s just that Korea is such a conservative place, and their generation did not even have a chance to consider these issues.

My mother was curious why gays and transgendered people in Korea didn’t function in a socially “proper” way. Though this may seem ignorant, I actually get her point. Social acceptance is tough–if not impossible–for the LGBT community in Korea. When it comes to one’s sexuality, it’s either they hide it or wave it around rebelliously, dressed in nothing but their underwear. Or sometimes even less than that. Dark stories of gay bars and saunas, as well as HIV and AIDS are the main reasons for the infamous reputation of queers.

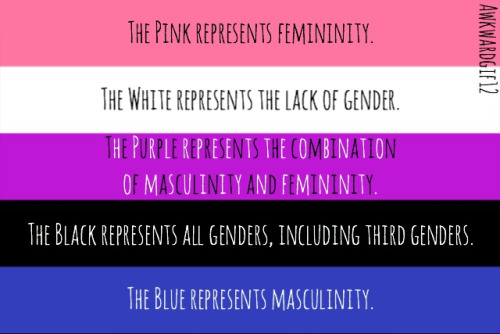

But even public events that support the queer have seemed nonsensical. I was excited to find out that there was a queer festival in Korea, and eagerly looked it up. Yet I was shocked to see pictures of people in the streets wearing underwear and other garments inappropriate for public wear, giving speeches of hatred and anger towards the society. There were even graphic signs depicting queer sex acts. I presumed that the queer festival is for everyone to enjoy, a means to change the society’s perspective. And I couldn’t help but think that the shocking images presented by the queers would only generate disgust. Even I didn’t want to take part in that. Being genderqueer or genderfluid has to do with more than just “sex.” It’s related to life itself and having different feelings in certain situations.

But even public events that support the queer have seemed nonsensical. I was excited to find out that there was a queer festival in Korea, and eagerly looked it up. Yet I was shocked to see pictures of people in the streets wearing underwear and other garments inappropriate for public wear, giving speeches of hatred and anger towards the society. There were even graphic signs depicting queer sex acts. I presumed that the queer festival is for everyone to enjoy, a means to change the society’s perspective. And I couldn’t help but think that the shocking images presented by the queers would only generate disgust. Even I didn’t want to take part in that. Being genderqueer or genderfluid has to do with more than just “sex.” It’s related to life itself and having different feelings in certain situations.

It may sound selfish but I simply want to live my life, to pursue my career. I will continue to relate to men and sometimes women. I might even be lucky enough to find a person who loves me for who I am and might get married, have kids. I don’t want to talk about my sexuality in a graphic way. I want to be able to joke about it in a light, open-minded way, and move on to discuss other more significant topics. My sexuality shouldn’t be the main thing that determines who I am. It’s simply a small part of me.

Nevertheless, I know it is a larger issue for other sexual minorities in Korea. Last year the United States legalized gay marriage. I wonder how many years will pass until Korean LGBTs gain social acceptance and legal protection.

I’m still discovering myself. It’s highly unlikely that I’ll tell people about my sexuality, especially my parents. The society’s not ready for my confession. Instead, I’ll try to look on the bright side: I can accomplish various tasks, not bound by my gender. I can relate to and have friendly conversations with people of all genders. I am fortunate that I am attracted to men only, which means I won’t attract unwanted attention because of the person I love. I can have my own unique style in fashion, creating a sharp contrast between my delicate physical features and my tough clothes. The possibilities are endless.

I know that I won’t ever get accepted by some people. And I even used to worry that I might get disowned by my parents if I ever told them. I also know that I’ll never belong in a certain gender. But I don’t need to know what gender I am to know who I truly am. I love myself, and that’s what matters.

Closing Notes:

- I constantly worry about whether there is anyone in this would who would love me. Men usually like “feminine” features in a woman, and aside from physical appearance, I have none. Women might be attracted to me, but not vice versa.

- I don’t want to undergo a sex change. I am comfortable in my own body. After all, I’ve been living in it for 17 years now. Now that I think about it, there might have been a time when I wanted a different type of…ahem, genitals, but now I love my body. I would hate to judge my body based on what others think of it, but it’s a fact that most men are physically attracted to women.

- I sometimes feel that my hormones have similar effects to those secreted inside a man’s body. Not much physical change, but similar feelings and desires. And puberty is a flood of such hormones. That’s one of the reasons why I exercise regularly.

- I like how many people on the Internet refer to others as “bro.” I like the sound of it. The term “사나이” (sana-e) means a “very manly man.” I once had a debate with my parents over whether a woman could be a 사나이. I lost.

- After having all these thoughts, I don’t feel the need for gender. We are attracted to whoever we are attracted to. There’s no such thing as LGBT, in that sense. There are just human relationships. If the feelings are mutual, good for you. We should feel free to act on our attraction towards someone (as long as it’s of legal age).

- I worry that I wouldn’t be able to exist if I tell people about this. Nothing would be left except for “that gay girl”(many people don’t understand the concept of the gender spectrum very well). People would see my actions and behaviors differently. I would wear dress shirts “because I’m genderfluid” and have a not-so-effeminate voice “because I’m genderfluid.” Nothing would’ve changed about me; it’s the same person they knew before I told them about my gender identity. But what would change is their way of seeing me and my behaviors. And, unfortunately, I doubt the word acceptance would ever enter the conversation.

Print This Post

Print This Post