Click To read Part I

By Ian Taylor Presnell

Everything was unbelievably clean and neat. In the bathroom all soaps and shampoos and brushes and toiletries were arranged from biggest to smallest. The toilet was almost humming it was so shiny, even the tiny spaces in between the tiles of the floor were clean.  It was as if nothing in the bathroom had ever been wet, no more than that…never even used. She stepped inside and picked up an orange Dove body wash to see if any had ever even been used, that they weren’t just props, that any of this was real. She turned on the water in the sink, and then quickly turned it off. She stepped back out into the kitchen, which on closer inspection was the same as the bathroom, cleaned beyond any one person’s capacity for cleaning. The motion light turned on again, but with the other stronger light there constant and controlled by switch it didn’t even register in Nat’s mind. It (her mind) was occupied by the shoe not eight feet away now. It was a blue sneaker of normal size, and with one step she would be able to see the rest. The shade was pulled down beyond it or else she would be able to see what was there from the reflection of her exact same window. She would have to move to see it, not even forward, she could just move to the side away from the wall to see the rest. So that is what she did—moved to the side away from both walls to see.

It was as if nothing in the bathroom had ever been wet, no more than that…never even used. She stepped inside and picked up an orange Dove body wash to see if any had ever even been used, that they weren’t just props, that any of this was real. She turned on the water in the sink, and then quickly turned it off. She stepped back out into the kitchen, which on closer inspection was the same as the bathroom, cleaned beyond any one person’s capacity for cleaning. The motion light turned on again, but with the other stronger light there constant and controlled by switch it didn’t even register in Nat’s mind. It (her mind) was occupied by the shoe not eight feet away now. It was a blue sneaker of normal size, and with one step she would be able to see the rest. The shade was pulled down beyond it or else she would be able to see what was there from the reflection of her exact same window. She would have to move to see it, not even forward, she could just move to the side away from the wall to see the rest. So that is what she did—moved to the side away from both walls to see.

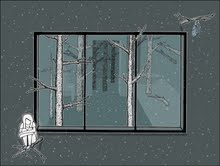

The day her father died she had been walking among the trees soaked from the rain in the forest not a mile from her house. This is where she did all of her grieving, alone in the woods. She made sure to go past where any other people walking in the woods might go, off the path away from any indication that civilization had ever even occurred. Away from all sounds, all people, all manufactured smells. She knew the woods like she really did live in the past. Sometimes she could almost imagine that she lived in some other century without malls or cell phones or commercials; it was easier when it was cold, maybe because a part of herself couldn’t imagine why she’d be out in the freezing woods when there was a warm house with a bed and food and water on tap not a mile (or two or three depending on how far she had walked) away.

She walked, feeling the pills smoothing a white sheet across her mind, thinking about a day in the summer when she was visiting from her apartment at school and had walked for hours but still had been unable to get away from all the sounds and smells and her phantom mother and her silent father and the boy at school who told her he wanted out, and finally after telling all the reasons, admitted there was someone else, and her favorite cat who used to be so energetic and rebellious and fierce who now just laid in the same spot on the cold cement floor in the basement of her parent’s house, mewing in pain, suffering for all the fights and all the nights he’d spent outside. And she had stopped and sat down in the dirt, crying for all of it, sobbing in great rolling waves so that when she thought she was finished, another wave would come, and she wasn’t even thinking anymore, just crying because it was coming in these great tsunamic waves, crying for everything and nothing, because she hadn’t cried in years, and it had built up and carried over, and it felt good, cathartic, like a release or a pan of boiling water spilling over the sides because it has to, because it must find somewhere else to go; more space for all the unstable combusting atoms that have finally reached their capacity like a city of 13 million people or a bar where not even one more person can squeeze into and nothing can move until someone leaves.

It was just beginning to subside—the waves—and she was wiping away all the snot and tears when she heard someone say hello, which startled her incredibly because she was inside of herself secluded in the middle of the woods. She instantly stood up as if to run away from the voice and all the rest of boy standing there, and maybe if it had been a man she would have run, (not because of the size or strength but because of the paralyzing self-consciousness acquired by all after a certain age) but it was only a small boy standing in the middle of the woods saying hello. Adults couldn’t be honest because of that consciousness; they could never really be themselves or see situations or even objects how they really were, and that same “hello” if it came from anyone but a child could have meant a hundred other things except for hello or even if it really did mean hello, her consciousness would change it to mean something else. He came closer.

“I’m Nathan.”

“Hi Nathan, I’m Nat.”

“Are you OK? I saw you crying.”

“No…yeah I’m fine you just scared me. I thought I was alone.”

“I heard you crying and came to see if you were hurt.” Nat smiled.

“Well I’m glad someone would have saved me if I was hurt.” The boy pointed over a hill.

“I live right over there. This forest is right in my backyard.”

“That must be nice.”

“Yeah it’s cool, where do you live?”

“I live on Orange St. by the entrance to the glen. That’s where I walked from.”

“Wow that’s far.” He seemed impressed. “Why were you crying?”

“My cat’s dying, and my boyfriend left me, and my parents are crazy,” and she walked and talked with this boy for an hour, and it was the first time in a long time she could remember that she genuinely enjoyed talking with another human being.

On the day her father died, walking in the woods she wished that she would run into the boy again. She had woken up early in the morning, and before even going to the bathroom she tiptoed over to her father’s room and checked everything like the nurse had showed her how. Her father’s arms were bruised and yellow on his hands and forearms from where the needles were repeatedly put into. He had barely opened his eyes these last few days, and when he did they looked glossy, as if they were drowning. Death really had a smell. The heart monitor machine hummed steadily beside her father. This was not her parent’s bedroom growing up. It had been suggested that her father move into the spare bedroom to fit the trundle bed and all the machines. At first Nat herself had been petrified of putting the thin needles into her father’s skin. Her father of course hadn’t wanted to move, but he finally agreed with a defeated wave of his hand. Nat had automatically opted for the pull-out couch in the living-room. It was closer to her father and basically she felt claustrophobic and insane in her old room. But she had eventually gotten the hang of it…the needles. She had never believed that death really had a smell… but it did. She remembers reading a dialogue in, “For Whom the Bell Tolls” where the strong old Spanish woman was trying to tell the American solider that death had a smell. But he didn’t believe it. Nat’s cat had died a few weeks after she had cried in the woods behind her house before the little boy had approached. She was waiting outside a shady plasma donation center in Reading, and by the tilt and hesitation in her mother’s greeting she already knew what her mother was going to say. She hadn’t cried then. It was something she had already accepted.

Her father was going to die. She had admitted this to herself, but admission was not acceptance as much as she wanted to think so. Nothing tragic was ever discussed in her family. The abortion, the miscarriage, the affair, her mother leaving with the other man six months ago were never actually acknowledged or discussed in any way. Death smelled like rotten food and the flowers blooming in Ivy Lane at her University in the spring that smelled vaguely of sex, and like the prostitute houses she would later walk by in Korea all mixed together but profoundly sad and different than all of these things. It was not a pleasant smell. Her mother had called Nat’s cell phone several weeks ago, but Nat couldn’t force herself to call her mother back. It would probably be easier after he died. She had no brothers or sisters and strongly felt that this was a substantial reason why she felt so deranged most of the time. It was 7 o’clock in the morning. She had been taking several of her father’s pain pills each day in the last few weeks. Every time she took one she loathed and hated herself beyond anything else she had ever done in her life. But she couldn’t stop. She had admitted that to herself at least. Pain killers were what some people called them. Pain killers.

She stood there concentrating on her father’s chest rising almost unnoticeably, moving the white eider blanket the tiniest bit up and down. The house felt empty, which reflected the emptiness inside her own body. Hollow. She felt hollow like she wasn’t even real, like she didn’t even really exist. Her father had refused food in the last three days. It would be soon. She knew that for sure. And without her mother she would have to deal with the burial; she would have to make all those obscene phone calls. The older lady across the street stopped by periodically with these elaborate casseroles that Nat thanked her for excessively and that just went bad in the refrigerator. She hadn’t had much of anything resembling an appetite either, lately.

Her father rasped in his sleep and wheezed and coughed, and for a moment Nat thought: ok this is it. He will die right now, and you will make those phone calls because there isn’t anybody else. And then you’ll go directly to the liquor cabinet and take a handful of your father’s pills and sit in the living room and wait for whoever came to come. But he breathed in again harshly. His face was sunken in and white and twisted in pain. Even in sleep he looked like he was in pain. She moved a step closer with one hand stretched out tentatively as if she were signaling for something big and massive to stop. Then she stopped in the middle of the room.

A vivid memory of this room just came out of the fucking blue in her head. Her father hefting the mattress (the same mattress the same mattress) against the corner of the room and then bending down to inspect the frame of the bed for the origin of these alleged squeaks he’d swore he heard when her mother’s sister and her sister’s husband had visited the weekend before in route to New England, where her aunt’s husband had some family. It was abundantly clear that her father didn’t like her aunt, and the tension that weekend was off the charts, Nat had felt even at 10-years-old. Her mother was in the other corner looking at a neutral spot on the floor in between Nat and her father.

“It’s something here that needs to be tightened. That’s all it is.” He was in the middle of the frame pushing his weight down on different spots. Her father had an array of tools spread out beside him on the floor. Nat thought that there were an excessive number and array of tools for something that just needed to be tightened. Her mother was looking at the floor, and Nat was standing underneath the doorframe. It felt like something that demanded that all the family be together for.

“Little bugger is here somewhere. I couldn’t sleep at all. Not a wink. Sounded like these vermin in Korea that no one in our platoon ever really saw because they just scattered back into the walls whenever anyone ever turned the lights on. Lowered our morale more than anything in that war. Those Korean rats or whatever they were. Our food always had these chunks bitten out of them too.”

“John.” Her mother looked how the word rigid sounds.

“What? I’m just telling you that the squeaks on this bed reminded me of those little mice that nobody ever really saw.”

“Natalie does not need to hear this.”

Without looking at either of them her father said, “I’m just telling her something about her father is all. Something that occurred in her father’s life that she might want to actually know about that…”

“She doesn’t want to hear about rats John.” Nobody but her mother ever actually called her Natalie.

Her father wheezing constant and the hum of the heart machine and the clock ticking the seconds further now too, all these sounds and Nat’s own silence and hollowness inside herself that she felt every time she took a breath. The smell of death and the abrupt coldness of that memory even though she felt hot, and the accumulation of all that had not been said in this tiny house. And never would be said, she thought. And that never would be said. She was suddenly angry at her pathetic dying father, for never doing anything individually traumatic enough to make her feel un-guilty now for the anger towards this dying old man. What could she actually say he’d done? Because it was harder to verbalize the trauma of the things that had never been done. It sounded ridiculous even inside her own head.

She walked outside of the room into the bathroom adjacent to her father’s new room. His last room. Shut up. She peed and washed and brushed and felt too dirty not to take a shower. And after the shower she dried herself and went into her old room to change. It had begun to rain. It was raining now. Her parents never loved each other. But Jesus mom. To not be here? To leave when you knew and could have just stuck it out another year. I hope you’re happy because God knows I’m not.. And I have to blame you two because if I can’t blame something then what’s my excuse? What about all these people I meet who had these blooming positive rewarding households growing up? And of course they’re these happy positive people in these recurring rewarding relationships who complain about like getting cut off one time in traffic three years ago. Why am I here mom? Why me?

She walked back into the bathroom and silently opened the medicine cabinet behind that mirror that reflected a thin unhappy girl who was attractive enough, but who couldn’t see that unless someone told her. And who fell for any guy who told her because she never was once commended on anything that she can remember, not once Dad, not even one nice memory in all these shit memories that come flying at me in this tiny creaking run-down house that smelled like death long before anyone was ever really up. She withdrew the white round bottle with her father’s name and the script running parallel all around the circumference of the bottle and withdrew two and then three and then four and swallowed them without any kind of liquid because she wanted it to feel bitter. She wanted it to.

Then she walked back out into the hallway looking at her father for what she did not know would be really the last time ever, and then she withdrew her coat from the closest and closed it in one motion, and put on her shoes and walked to the refrigerator and withdrew a 20 oz. bottle of Pepsi and watched herself pour ¾ of it down the drain and then filled up a tiny bit of it up with Cranberry/grape juice and then the rest up with vodka from the liquor cabinet (all these irrelevant details that she would remember so vividly when she came back hours later to find her dying father dead without ever saying that she was good enough).

Of course the ankle was attached to a leg, and the leg to a body, and the body to a neck choked by some sort of cord attached to a hook on the ceiling. There was obviously a face too, but it was facing out towards the window, and what did the face matter when the body was limp hanging from a hook in the middle of the room? He was wearing shorts and a green shirt, and she could tell that he was white, and that he hadn’t done it very long ago. The bed was made and everything on the table and bookcase was arranged like the items in the bathroom. There wasn’t much—a few books, a few clothes hung up, a laptop, a chair, a table, a plant on the windowsill, a lamp, impersonal like a hotel room… like he only came here to sleep. The bed and table were arranged differently than in her apartment, but the differences were minimal because there was only so much you could do to a 10×15 room if you wanted space to move around. And she knew too that the view would be identical if she looked out the window, but to look out the window she would have to walk past the body, and when she turned back around to walk back across the room she would have to look up at the face that didn’t care anymore about the view, didn’t care about anything anymore or maybe cared TOO much.

It was the same: to care too much, to not care, they were both defenses against that world out there past the view, that could never fully be revealed because it was too big and no matter what you did or said or who you were with or where you went in it you felt small and irrelevant and expendable because you couldn’t see it all, or even a tiny piece. That’s the only thing our consciousness confirmed—that we were unimportant and thus whatever the age between boy and man was the result of that consciousness. And this was what some people did. Some people really did this. To refuse it. To give it back. To say: I’m done playing. I quit.

We want to be happy, to be important but we can’t be and then we lower happiness to contentment and importance to popularity and then contentment to feeling not bad and popularity to having one or two true friends, and then to not feeling horrible and just having a stranger to talk to, and we lower our standards more and more until we can’t lower them fast enough to keep up with the way we feel inside, and then we’ve quit anyway, even if we don’t take ourselves out, is what Nat is thinking essentially, standing there looking at the dead hanging limp body.

Ian Presnell is a capricorn. He’s way younger than he looks. He’s just decided that he’d be happy being either a famous comedian or a famous novelist. If he had a gun to his head he’d have to say that David Foster Wallace, Ayn Rand, Cormac McCarthy, A.M. Homes, Jonathan Franzen, and Hemingway are his favorite authors. More than anything he loves sleep, flirting, alcohol, books, being funny, food, and animals. if you see him say hello

Email author with any comments ipresnel@gmail.com