By David Wills

During my three years in South Korea, there wasn’t much the locals would say to me about China that wasn’t overwhelmingly negative, bordering on the outright racist. Even the very youngest students would tell me about the “dirty” Chinese, who sit around watching each other defecate, stopping only to eat babies or steal something from Korea. Of course, Korea isn’t exactly a land of open-mindedness and enthusiasm for its neighbours. Even by the standards of Asia – where animosity between nations is commonplace – Korea is notable for its xenophobia, its paranoia, and its sheer contempt for people that look, act, or speak differently to those of the one true bloodline.

Yet it surprised me when I arrived in China and found that the opinion of Chinese people towards Korea and Koreans (and I’ll state now that I’m definitely referring to South Korea, rather than China’s ally up North) was unanimously positive. Now, I can’t pretend to have taken a sampling of the population as a whole, but I have taught in China for a year and a half, and could count more than five hundred people having told me about their fondness for all things Korean.

Of course, there are stereotypes, but these are nearly always positive (or as positive as stereotypes can be): Korean men are handsome and chivalrous, Korean women are cute and feminine, Korean people treat their elders with the utmost respect, and spend every minute of their lives with their families, whom they love and honor and are faithful to…

You might have guessed by now that China’s perception of Korea doesn’t come from any actual experience of real life. It is gleaned almost entirely from Korea’s two big cultural exports – the overly emotional, sugary K-pop song (and the videos that go hand-in-hand), and the ‘melo-dramas’ that are about as artificial, as healthy, and as addictive as crystal meth.

Girls’ Generation – known in China by their Korean name, Sonyeo Shidae – may not be as popular in China as Lady Gaga, Justin Bieber, or Eminem, but their hits are ubiquitous and blast from shops, cell phones, and car radios. K-pop shows are all you’ll ever see on the store model of the latest TV, and China’s homegrown “talent” is now comprised largely of K-pop knock-offs. Perhaps the more surprising success is that of Korea’s dramas, which are sweeping Asia more like a tsunami than a wave. Dae Jang Geum – the most popular – is bizarrely taken by a lot of Chinese as near documentary-like coverage of life in Korea, and is the favorite show of stony-faced President, Hu Jintao, who once quipped that he would watch every episode if he wasn’t so busy leading China. The theme song is one of the most popular songs in China right now, and has been covered by numerous Chinese artists, including the winner of China’s Super Girl TV show (which aims to produce China’s answer to a K-pop idol…).

Girls’ Generation – known in China by their Korean name, Sonyeo Shidae – may not be as popular in China as Lady Gaga, Justin Bieber, or Eminem, but their hits are ubiquitous and blast from shops, cell phones, and car radios. K-pop shows are all you’ll ever see on the store model of the latest TV, and China’s homegrown “talent” is now comprised largely of K-pop knock-offs. Perhaps the more surprising success is that of Korea’s dramas, which are sweeping Asia more like a tsunami than a wave. Dae Jang Geum – the most popular – is bizarrely taken by a lot of Chinese as near documentary-like coverage of life in Korea, and is the favorite show of stony-faced President, Hu Jintao, who once quipped that he would watch every episode if he wasn’t so busy leading China. The theme song is one of the most popular songs in China right now, and has been covered by numerous Chinese artists, including the winner of China’s Super Girl TV show (which aims to produce China’s answer to a K-pop idol…).

Korean food is popular in China, too, with even the smallest, most provincial cities serving up hansik as a cool and vaguely exotic luxury. Korean electronics and vehicles are seen as being on the cutting edge, albeit a more affordable option than imports from Japan (for which most Chinese share a less enthusiastic opinion). They also have the reputation of being far more reliable than anything with the dreaded “Made in China” label, which is even feared by the average Chinese person. Fashion is a huge import, too. Shops across China sell “cute Korean girl arm warmers”, seemingly unaware that the majority of Korean “girls” who wear these are in fact probably over of the age of sixty, and Chinese girls wear t-shirts with bad Korean written on the front almost as often as Korean girls wear ones with bad English. It’s not just the girls, either. Young Chinese men are preening themselves in pursuit of that modern Korean style, complete with plunging necklines and perfectly coiffed hair.

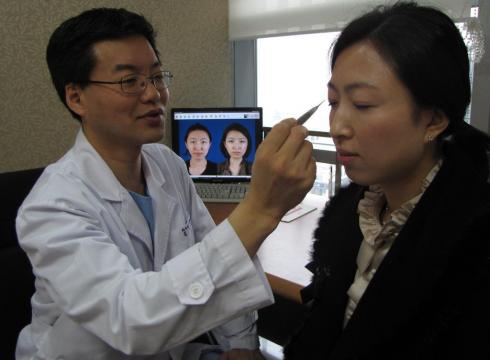

But there is one more idea that is labeled “Korea” in the mind of almost all Chines e people, and that is cosmetic surgery. In fact, it is fair to say that – above even Girls’ Generation and Dae Jang Geum – it is this that pops into the mind when the word “Korea” is mentioned. I have numerous times told my students that I lived in Korea, and their reply is invariably, “Korea…? Ah yes, surgery!” It’s as though the two words are inseparable.

e people, and that is cosmetic surgery. In fact, it is fair to say that – above even Girls’ Generation and Dae Jang Geum – it is this that pops into the mind when the word “Korea” is mentioned. I have numerous times told my students that I lived in Korea, and their reply is invariably, “Korea…? Ah yes, surgery!” It’s as though the two words are inseparable.

It’s hardly surprising that this idea would be so prevalent in the mind of people whose exposure to Korean culture pretty much extends to K-pop and TV dramas. The funny thing is, Chinese – along with much of Asia – are in awe of “the Korean look”, referring to big eyes, high cheek-bones, milky white skin, and small, youthful features. Yet, this look is about as Korean as I am. The great irony is that these men and women who define Korea in the modern age are actually trying to Westernize their faces. Through China, Japan, Malaysia, and Thailand, millions of people are worshipping these K-idols as much for their hybridized Western-Eastern features as their music or acting abilities.

It is odd, then, that while Korea tries to spread its culture around the globe, it does so with young actors and singers that are trying hard to look decidedly not very Korean, acting in dramas that are unfaithful to life in Korea, and singing songs that are imitations of Western music… But, then again, Korea is a modern Asian nation, struggling with its new identity. It is what it is, and it’s presenting that new face to the rest of the world with startling success. It is the envy of Asia for the time being – having usurped Japan’s throne as the king of cool – but is it really presenting itself in the best light? And does the average Korean person look anything like their K-pop idols?

Plastic surgery is more common in South Korea than in any other country. It is not generally covered by health insurance, and so it’s difficult to know how many people exactly have undergone procedures, but various studies and reports claim that between twenty and fifty percent of adult women in South Korea have received some kind of treatment, with likely the majority of twentysomethings falling into this category. The most popular treatment is by far and away a form of blepharoplasty, known as the double eye-lid snip, which makes the recipient’s eyes look bigger, followed by operations to enlarge the bridge of the nose. Other popular treatments include breast enhancements, penis-enlargements, butt-implants, liposuction, botox (to atrophy and shrink cheeks, rather than to remove wrinkles), the cutting of nerve in the leg to cure “radish-shaped calves”, and jaw-shaving, to give a thinner, more Western-shaped face. So whilst the average Korean person is born without what is now known as “the Korean look”, there are now plenty of people walking the streets of Seoul with their faces and bodies surgically altered to look like their favorite stars which of course represents the new “Korean Look.”.

Unsurprisingly, with the rest of Asia looking in awe at Korea’s beautiful people, the nation is marketing itself as a destination for surgery. The travel agents who organize trips to Apgujeong in Seoul, where there are more than 400 plastic surgery clinics, call it “the plastic surgery Mecca of Asia”. Some clinics claim to have between 20-30% of their patients come from oversea s, thanks in part to recent shifts in the value of the Won. Daegu, too, is selling itself as a “Medical Tourism” city, with the city government’s own website declaring (in various languages, including both simplified and traditional Chinese) that plastic surgery prices are significantly cheaper than in Seoul, and comparing prices with surgery in the United States, Japan, and Singapore. It boasts that, “With the recent Hallyu fever… foreigners, especially from countries in Southeast Asia such as China and Thailand, are visiting Daegu for medical procedures.” There is also a convenient link to the Meditour website, which arranges package tours from all over Asia to Daegu.

s, thanks in part to recent shifts in the value of the Won. Daegu, too, is selling itself as a “Medical Tourism” city, with the city government’s own website declaring (in various languages, including both simplified and traditional Chinese) that plastic surgery prices are significantly cheaper than in Seoul, and comparing prices with surgery in the United States, Japan, and Singapore. It boasts that, “With the recent Hallyu fever… foreigners, especially from countries in Southeast Asia such as China and Thailand, are visiting Daegu for medical procedures.” There is also a convenient link to the Meditour website, which arranges package tours from all over Asia to Daegu.

Is it any wonder, then, that the average Chinese person finds it hard to separate the image of Korea from plastic surgery?

Korea sells itself to its neighbours very carefully. Granted, this is not a decision made by the average person on the street, but instead by the managers and PR people behind acts just like Girls’ Generation and TV shows like Dae Jang Geum. Whether or not political relations between these countries sour, the money and effort that these people invest into tailoring Korean artists (and therefore, by proxy, Korean people as a whole) to countries like China, Japan, Thailand, and Malaysia, ensures that certain stereotypes will, for better or for worse, continue in the minds of the populations of these countries. You can bet that for as long as these stars stay in the limelight throughout Asia, there will be people flying to Seoul and Daegu to have themselves cut to look like their heroes. Thus, for the foreseeable future, Chinese people will continue to think of the average Korean person as a cutesy K-pop idol, who bursts into tears or rage at the slightest provocation, and is comprised mostly of medical-grade silicon.

______________________________________________________

David on 3WM: http://thethreewisemonkeys.com/2011/10/24/the-dog-farm-a-novel-about-life-in-korea-by-david-s-wills/

David S. Wills is the editor of Beatdom magazine and the once-anonymous blogger behind controversial K-blog, Korean Rum Diary. He spent several years living and working in Daegu, South Korea, where he gained the inspiration for The Dog Farm, his first novel.

Print This Post

Print This Post