By John M. Rodgers

A few weeks ago on a Saturday afternoon, an email came in from an acquaintance who comes into contact with most Korean-related content on the Web and then disseminates it via his blog. He’d just gotten, he wrote, “the oddest call” from a man convinced that he was about to be arrested for uncovering a “human traffiking/illegal teacher scam.” Perhaps I’d be interested in contacting the individual, was the suggestion with contact details. This began what has been a bizarre and frustrating process of trying to get to the bottom of the story.

After doing some cursory research on the individual, I called him. What followed was a manic 66-minute monologue as he explained his allegations against an English Village on Jeju Island that had left him out of several thousand dollars in pay in a scheme that stretched back at least six years and included some 60 other bereft teachers whose names are on a list at the Korean Labor Ministry. Human trafficking, fraud, foreign child labor, neglect and abuse were among the allegations mentioned during the call with numerous references to specific incidents that evidence in his possession allegedly supports.

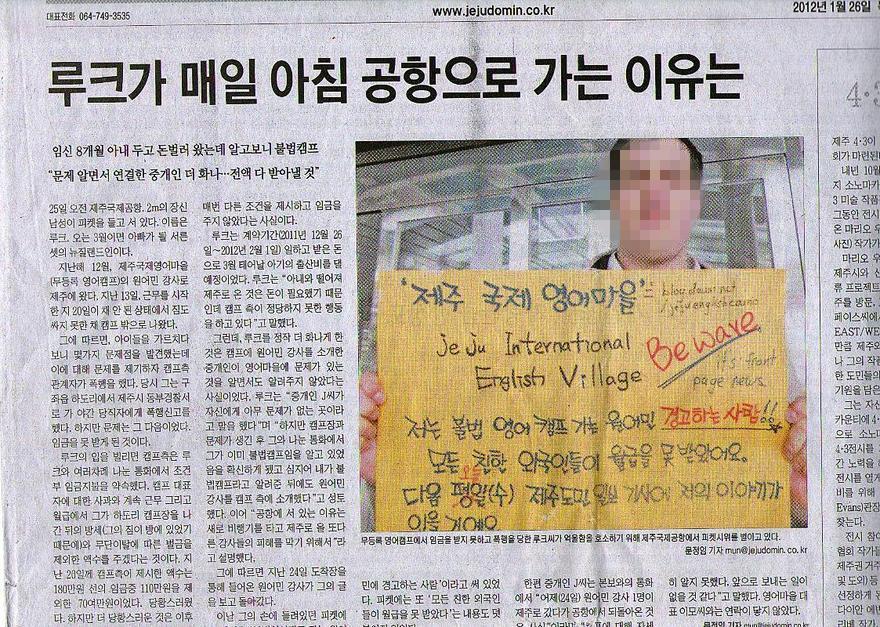

Moreover, the individual believed that the Korean Cyber Police would be taking him into custody at any moment and that the evidence he had in his possession and posted online would be compromised and potentially destroyed. Thus, the evidence needed to be secured and then put to the public’s attention. Research before the call led to news articles in the Korean press that detailed the same  charges and showed pictures of the individual at the airport with a sign advising passersby of the transgressions.

charges and showed pictures of the individual at the airport with a sign advising passersby of the transgressions.

The individual had been charged with defamation, he said, for posting a picture online that showed potential sexual abuse by individuals involved with the English Village. It’s unclear how the airport protest was received given the all encompassing defamation laws on the peninsula. A later look at the individual’s Web site revealed numerous posts detailing the crimes committed at the village and images of the village’s owner and others (all dangerous in the defamation domain). That site, as the individual predicted at the time, was censored less than a week later and all of the content rendered useless. Yet the information had been successfully passed on to others and has been posted on a U.S. Web site by a 2006 victim who came to teach at a summer camp and ended up working a month of 12-or-more hour days and going home without a cent. “The conditions were terrible for teachers,” said Mazarine Treyz, now 33 and living in Texas. “We worked insane hours—I bent over backward—there was no food…it’s still hard to talk about now.” Treyz went on to say that the behavior of managers was disturbing: “I couldn’t believe the yelling—there were times when they would just scream at us as loud as you can imagine…just yell at us for nothing.”

Treyz finally called the police one night after being berated by a teacher coordinator: “The teacher coordinator Mr Song cracked down on me and screamed at me (for absolutely no reason) on the night of August 20th so I cried and called the police but no one there could speak English, so I hung up,” wrote Treyz. According to Treyz, the next day the police arrived at the village to see what was going on: On August 21st two policemen showed up at the camp around 2 p.m., (I was taken out of my class to give them my passport), and through [an interpretor] I told them how upset I was and how no one was getting paid, and she told them about all of the other Korean teachers were getting scammed as well.” Despite the visit and a “raid” by officials two days later, nothing happened. On August 28, she was driven to the airport by a policewoman who offered to let her stay “a few days longer” to try to get the $4,000 she was never paid. Treyz says she was “broken down” psychologically by the experience and realized she’d never get her money. “I was traumatized by the treatment and didn’t expect to get justice,” she said. “I felt like I had some sort of PTSD but eventually talked myself out of it.”

Treyz who is still a teacher and also does Webinars, said she’d decided to move on but hoped people found out how corrupt the Jeju Village is and that no one else falls prey to its nefarious activities: “I’ve moved on but I hope no other teachers or children get hurt.” Treyz added that she was doing what she could to get all relevant evidence on the Web site.

In 2007, the Korea Herald posted an article about this business that went into specific details about its illegal activities and suggested collusion with authorities was rampant. Teachers who’d taught at the camp detailed “being screamed at and threatened by the director” and offered accounts of negligence on the part of Korean authorities to take action on the case, referring to the Labor Department, Immigration and the police.

Chris Gelken, the Herald reporter who wrote the article, said he received threats from the village’s owner–much like he did from other academies he scrutinized–that never came to anything. “I was personally threatened with a lawsuit, but that didn’t happen. In fact, almost every hagwon I wrote about in Korea warned of a lawsuit,” said Gelken who now works in Hong Kong. Recent assertions that he had faced a backlash at the Herald after the story ran seem unfounded; Gelken said in response to a question about such editorial reprimand: “None. My boss was always very supportive of our ‘campaigning’ style of journalism.”

The individual who contacted me in a panic portrayed the same conduct by authorities as Gelken did in his article, saying they’d been “turned” one by one and failed to take any action despite reams of evidence and repeated reports of abuse and unpaid wages.

Another teacher contacted, Jim Cuthbert, 32, said his documents had been fraudulently altered by the managers at the business. “They stamped our passports and changed our contracts,” said Cuthbert a British national. Cuthbert also confirmed the conditions at the camp. “The food was awful and so was the A.C.; they didn’t deliver on anything,” said Cuthbert. “And they didn’t pay anyone, foreign or native.”

Speaking with Todd Thacker the current editor-in-chief at the Jeju Weekly, it was evident he didn’t feel the story was safe to deal with after he’d been approached by the same individual who reached out recently. “The story is a good story,” said Thacker, “but we did not touch it because we don’t want to be sued.” Thacker said the Korean papers that covered the story had their lawyers but his publication didn’t. “Those Korean papers have their own staff of lawyers, they have legal resources…we don’t have that,” said Thacker.

The individual who is now on a crusade to expose the village went on to say his attempts to get other Korean English dailies to cover the story had failed. “The Korea Herald and the Times will not cover this,” he said. He asserted that evidence proved the executives at the Korea Herald were involved with the owner at the Village and had actually presented him with an award after the Herald ran the critical article. A picture posted on his Web site showed such a ceremony but independent verification of the identities of individuals has proved difficult and dangerous.

A call to the managing editor at the Korea Herald was met with a curt response: “I think I’ve discussed the story with my reporters but I can’t remember. Talk with them.” In a discussion with Herald reporter Paul Kerry it was clear that the paper wanted nothing to do with the story for a number of reasons. “We can’t go on what was brought to us by [individual] because it’s not reliable,” said Kerry referring to the information that was presented and the questionable background of the individual which includes legal issues outside Korea. Additionally, Kerry said the paper doesn’t have the manpower to cover such a sensitive and complicated story. “We don’t have the resources to cover a story like this,” said Kerry. “We can’t send people down to Jeju to investigate.” Kerry added that the story is old and has been covered which makes it a hard sell to editors. In response to the allegations made about the Herald’s connection to the village’s owner, Kerry explained that the Herald had never presented the business owner with any award. “The Herald Business gave him an award. Herald Business is owned by Herald Media, which has our CEO. The Korea Herald does not have a CEO. We’re just a smaller part of the same company as the Herald Business,” Kerry said.

Circumstances following the initial contact with the aforementioned individual led to a lapse in communication. It is clear the site is down and other sources still in contact with the individual say he will be brought in for questioning and he has confirmed that defamation charges were brought. He is still communicating with people so it is clear that he has not been detained as he initially feared.

Contact with more recently wronged workers at the camp led to a Colleen Myers who was an English teacher  and chaperon for 14 American Volunteers from July 20, 2010 to August 23, 2010. According to Myers, the camp paid for all of the plane tickets and the adults were paid in addition for teaching the Korean children English. The American children ranged in age from 12 to 19 years of age. Myers said the volunteers were worked like slaves and “were expected to be with the Korean children 24 hours a day.”

and chaperon for 14 American Volunteers from July 20, 2010 to August 23, 2010. According to Myers, the camp paid for all of the plane tickets and the adults were paid in addition for teaching the Korean children English. The American children ranged in age from 12 to 19 years of age. Myers said the volunteers were worked like slaves and “were expected to be with the Korean children 24 hours a day.”

Another complaint was the food: “we had to eat Korean food. Some of the American children would go days without eating because they could not tolerate eating rice all the time and the other strange things served. The camp owners said it was in our/their contract to eat their food but the children did not sign any kind of contract. Finally, (2 weeks before we left) we talked them into buying some bread, peanut butter, jam, cereal and milk.” According to Myers, the American kids began to rebel, skipping classes and events which led to conflicts with the ownership. “After a couple of weeks some of the American children would not get up and go to class or they would skip out and leave the camp for the day. When this started to happen the camp owner started to threaten that they would cancel our flights back home and we would be on our own to find a way back to America,” said Myers

In the end, the group persevered and made it back to America thankful and in one piece. “We stuck it out but it was the hardest 5 weeks of my life. I have never been so glad to see the American flag and know I was back in the United States,” Myers said.

As Jeju Island ushers in Jeju Global Education City (JGEC)–where it hopes to educate youngsters from around Asia (and maybe the world)–it certainly does not want to tarnish the embryonic image of the island and JGEC. This is big time with the likes of UK and Canadian private schools laying foundations on and making large investments in the island and Korea. It would serve the Jeju and Korean central officials well to clamp down on any shady individuals running questionable educational facilities. Given the fact that Korean news outlets have covered this story within the last few months, one can only hope that the issue raises some eyebrows in the offices where the real decisions are made. That is the only way anything will be done.

Print This Post

Print This Post