By Davis Wills

A few weeks ago, a couple of articles popped up on Google News that brought the name “Ieodo” once again to the attention of the world. Although admittedly there wasn’t much substance to these articles and they probably only went to print because it was a slow news day, it was enough to bring a collective groan from Korea’s expat community, and doubtless there were a few mentions of the “new Dokdo”, as yet another pissing contest continued between South Korea and one of its neighbors.

It appears South Korea has the national equivalent of Short Man Syndrome (this despite its population being taller than people in either of its big neighbors – China and Japan). It is sandwiched between powerful countries with bigger populations, more military might, and who’ve always had a greater influence over matters of global importance. The same can also be said of North Korea, whose brash actions and needless aggression are a painful cry not just for attention, but to inform the world that it has power and should not be ignored. History has not been kind to the Korean civilization, and it has been invaded and isolated for most of its existence. Yet in a remarkably short period of time, the southern half hauled itself from war-torn poverty to astounding affluence; and not just that, but it has become one of the richest nations on earth, sending its much vaunted Wave around the world to spread word of its new position. Koreans can be justifiably proud of their country’s progress.

But justifiable pride is something entirely different from rampant, aggressive nationalism, of which Korea has no shortage. Much is made of its hostility towards Japan, and to a lesser extent, China. This is often waved away by the fact that these nations have given Korea so much grief in the past, but even the United States, whose armed forces protect the nation, is a frequent target of Korean anger. It is classic Short Man Syndrome: acting with aggression towards a stronger or bigger entity to compensate for your own perceived weaknesses or flaws.

Korea’s squabbles with its neighbours are a thing of confusion, frustration, and mockery for foreign onlookers. But set in historical context – informing the aforementioned Short Man Syndrome – it is not a great surprise to see Koreans so ready to fight over apparently trivial matters, and to display incredible tenacity over the silliest of arguments. It constantly feels the need to assert what power it has, and to scrap for everything it can. Appearing weak is equated with returning to the past and once again being powerless.

This has been demonstrated most ridiculously in the country’s battle to rename the Sea of Japan. It is embarrassing that Korea honestly believes it has the right to change the English language, never mind the fact that it wants the language changed to make Korea the center of the world – with t he Sea of Japan becoming the East Sea (despite being west of Japan, and at various other compass points in relation to other countries).

he Sea of Japan becoming the East Sea (despite being west of Japan, and at various other compass points in relation to other countries).

The most contentious and best known of Korea’s pissing contests is that over the Liancourt Rocks, known in Korea as “Dokdo” and in Japan as “Takeshima”. The absolute fanatical devotion Korean people have towards this islet is astounding, and has become a constant source of mockery in recent years. It is very much like watching the short man in the bar get into a pointless fight to restore the dignity he never lost, while his perceived opponent just shakes his head in disbelief.

Now they are at war with China over something even more trivial: the Socotra Rocks, known in Korea as “Ieodo” or “Parangdo” and in China as the “Suyan Rocks”. This is nothing new; the two countries have been negotiating over the “submerged rocks” for decades, and even Japan had a claim to them early in the last century. But in March, Beijing once again irked Seoul by daring to suggest that negotiations might lead to a peaceful outcome. Lee Myung-bak immediately informed the press that they belonged to Korea and it was that simple. Diplomacy, apparently, is unnecessary.

But what are the rocks and why – for reasons other than Korea’s Short Man Syndrome – are the two countries arguing over ownership? The Socotra Rocks are indeed a submerged set of rocks that are often referred to as a reef or an islet. Lying 4.6 meters below the ocean’s surface, they are only visible in extreme weather. They have a place in Korean folklore thanks to their relative proximity to Jeju-do, where the local fishermen believed that seeing the rocks would mean the end of their life was nearing. In 1900 the rocks were discovered by a British ship (called the Socotra, hence the name), and from then on appeared on maps purely because of the danger they posed to passing vessels.

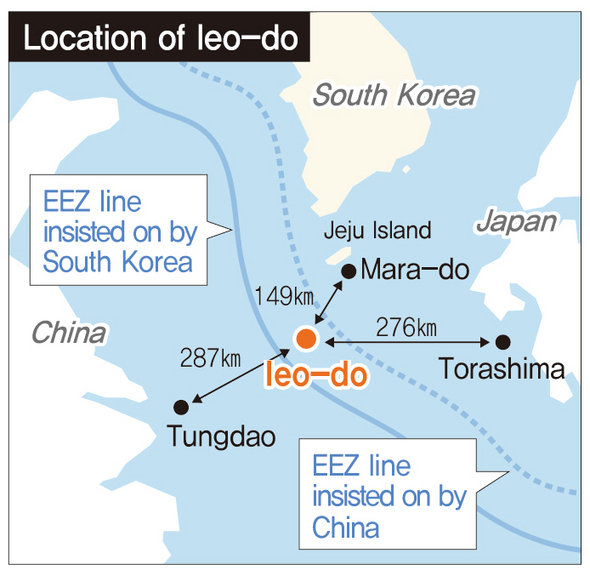

The rocks lie in the East China Sea, about 90 nautical miles from Korea’s nearest territory, Mara-do, and 155 nautical miles from China’s Yushandao. (Incidentally, Japan’s nearest island is Torishima, which is 171 miles away.) The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea states that a country has control over the use of  marine resources extending 200 nautical miles from its shores, unless of course that boundary overlaps that of another country.

marine resources extending 200 nautical miles from its shores, unless of course that boundary overlaps that of another country.

In this case, negotiations determine who can use these resources. Yet, after 16 rounds of negotiation, China and South Korea have come to no conclusion.

Perhaps that has something to do with the fact that one of the sides in the negotiations is so sure of their claim that they have presumptuously gone ahead and built a giant structure on top of the rocks. The Socotra Rocks are no longer four and a half meters below the surface of the sea, as they are now the foundation of a man-made structure that extends well above sea level, featuring a helicopter landing pad and a state-of-the-art research laboratory. No prizes for guessing that it was South Korea who swooped in and built the station.

This move might appear presumptuous and needlessly provocative, but then Korea also has built upon the Liancourt Rocks, installed a police force, cell phone coverage, given it naval security, made it a tourist destination, and even turned it into an impressive pollution producer. So much for civil negotiations. Apparently it is fine to simply take what you believe you have the right to take, whilst warning others of even coming near the disputed areas (both Japan and China have had good tongue-lashings for daring to venture too close to these hotspots), or being as reckless as to print a contradictory stance in a textbook.

China has responded by simply, and rightfully, condemning Korea’s belligerence on the matter, and pointing out that Korea would probably be unhappy if China had simply taken control of the islets and built upon them. They assert that peaceful negotiations are in the best interests of both countries, and Korea’s actions have threatened that. China doesn’t want to fight, but if pushed then it is not afraid of war with South Korea.

But there is a problem on the horizon for South Korea, aside from the extremely unlikely possibility of a military scuffle. As mentioned above, if the disputed land (or submerged rock) lies within 200 miles of your shore, you have a claim to it. Beyond that, it stands to reason that the nearest nation would then have the greater claim, and that seems as good a way to settle the situation as any, right? Except that for Korea this might not be the best solution. Certainly, by this logic Korea has the greater claim to the Socotra Rocks. They lie closer to the Korean mainland, and to Korea’s nearest island, Marado. But not so Dokdo: The distance from mainland Korea is 116 nautical miles, while it’s only 114 nautical miles to Japan. Korea would then surely have to acknowledge that it has been illegally occupying Japanese territory for almost sixty years. That would prove highly embarrassing for a nation whose identity seems so closely tied to Dokdo.

Korea’s construction of the controversial platform occurred back between 1995 and 2001, and drew little more than an obvious comment by the Chinese Foreign Ministry, which referred to the move quite rightly as “illegal”, a reaction similar to that of the Japanese during Korea’s long occupation of the disputed Liancourt Rocks. Various reports at the time refer to the issue as a “territorial dispute”, but is it even possible to have a “territorial dispute” over a submerged rock?

The answer is no, because anything that lies beneath the sea is not a country’s territory. However, as the rocks fall into both nations’ Exclusive Economic Zones, what they are debating (or rather, what they were debating prior to Korea’s invasion and occupation) is the right to claim these as part of their EEZ, and therefore exclude the other nation from utilizing it or nearby resources.

So now, on one side of the Korean peninsula there is the battle for Ieodo, which is closer to Korea than China, and on the other side there is the ongoing fight for Dokdo. But neither China nor Japan seem particularly interested in fighting over these issues, and it’s hard to see either side risking a war. In Japan they simply insist, “It’s ours,” and continue to print maps and books that assert that fact, in spite of provocations by Korea that  amount to military occupation. In China they don’t even want the Secotra Rocks; they just want Korea to cease its infringement upon what they consider to be their Exclusive Economic Zone.

amount to military occupation. In China they don’t even want the Secotra Rocks; they just want Korea to cease its infringement upon what they consider to be their Exclusive Economic Zone.

Korea is doing itself no favours, then, with these harsh tactics. “Taking what’s ours” might seem fair and logical in Seoul, but would they be as ready to accept the same of their neighbours? China has already thrown its weight around in the South China Sea, appearing to the whole world as some giant bully intent on gaining ownership of the oil that is believed to lie underneath. Few would argue that China’s actions were needlessly provocative, as it attempted to bypass diplomatic channels and simply take what it wanted. Yet few are saying the same of Korea, whose tactics seem alarmingly similar to that of their apparent enemy, China.

Says Park Chang-kwoun, Senior Research Fellow at the Korea Institute for Defense Analyses:

Ieodo is geographically closest to Korea and falls under Korean jurisdiction. But China, which has territorial disputes over seas with many other countries, is now arguing that Ieodo comes into its jurisdiction. To respond to this effectively, we need diplomacy based on power. And that power comes from the navy. For that, it is necessary to build a naval base on Jeju Island.

There is little danger of a war breaking out between China and South Korea, despite an October 2011 article in the Global Times threatened South Korea with “the sounds of cannons” (a threat oddly reminiscent of another of South Korea’s neighbors). The Socotra issue, coupled with that of murderous fishermen and the repatriation of North Korean defectors, will test the two nations’ relationship. But as China grows, it is certainly attempting to assert its dominance in the seas around its borders, particularly in what it views as its continental shelf, and it certainly won’t wish to appear weak by allowing such an obvious and illegal assault as that which Korea has perpetrated. Seoul would do well to choose its battles, even with the backing of the US military, and perhaps it would be best to keep going with their inexplicably passionate campaign for ownership of the Liancourt Rocks, while returning to the negotiating table and settling for a reasonable and peaceful conclusion to the Socotra debacle.

______________________________________________________

David on 3WM: http://thethreewisemonkeys.com/2011/10/24/the-dog-farm-a-novel-about-life-in-korea-by-david-s-wills/

David S. Wills is the editor of Beatdom magazine and the once-anonymous blogger behind controversial K-blog, Korean Rum Diary. He spent several years living and working in Daegu, South Korea, where he gained the inspiration for The Dog Farm, his first novel.

Print This Post

Print This Post