By Iwazaru

Not too long ago, I was sitting aboard an Asiana Airlines flight some 37,000 feet above earth on my way from Seoul, South Korea to New York’s JFK Airport where I would catch a flight to Boston and then a ride to northern New Hampshire. During the flight I had plenty of time to contemplate the transition from a frenetic, wired city of more than 10 million people to a bucolic town (pop. 4,044). I’d be staying at a relative’s home more than eight miles down a road that ends at a boat launch on the state’s largest lake, Lake Winnipesaukee.

“No Internet here,” my older brother told me during a call before my arrival.

Having lived in Seoul for more than five years, it is always a jolt to leave the buzz of the metropolis for a rustic setting where the silence and your heartbeat in the middle of night can be deafening. I often find myself feeling awkward in my first days (jet lag mostly) and weeks (cultural and idiosyncratic confusion) back in the country of my birth.

Handing over and receiving money with two hands; bowing to acknowledge people; hoping to get all kinds of side dishes with cheap meals— these are the things that I suppose people mean when they refer to reverse culture shock.

As I rode north on Interstate 93 in my brother’s Volvo wagon, I gazed at the nascent spring landscape, realizing that a new beginning was under way in nature and my life. How would I adjust?

Stopping in Concord (the state capital) to stock up at the local supermarket, I got lost in the multifarious aisles, unsure of what to put in the cart — “There’s so much stuff,” I kept thinking — listening for the man who calls out “sale” in the meat, seafood and produce sections of every Korean supermarket, prompting the usual push and shove of fervid female shoppers. Yet the store was rather quiet and vacant as closing time neared; a perfect time to shop, my brother advised. Our conservative shopping spree came to $117.52.

Well stocked, we arrived at the 1825 Cape-style house under cool star-filled skies. The pleasant smell of burning wood permeated the old home and the wood floors creaked underfoot.

Usually, I struggle to sleep after flying for more than 10 hours — jet lag twists the internal clock — but this night I drifted smoothly off and woke in the morning feeling rested — though misplaced. Strolling into the woods, pine and fallen leaves filled the air with familiar scents and two white-tails bounded off over a stone wall that winds behind the house. No din of traffic. No buzz of people rushing about.

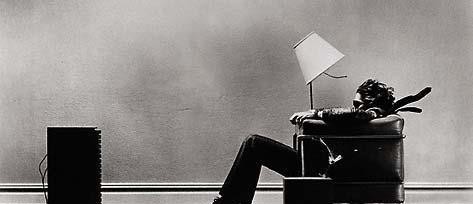

As my first day unfolded, there was some oak to be cut, moved and split, a process that is salubrious in its corporeality—everything is physical, methodical, precise. Such work slows down the mind, effaces the urge for digital updates and takes one back in human time. In the evening, as temperatures dipped into the low 40s, a fire needed to be kindled and the wood served its purpose gloriously, crackling and humming in the fireplace, illuminating the living room with a warm, golden hue, offering more reward for the work done.

In Asia there was no need for a car. Korea’s public transportation is astonishing: ubiquitous, modern, fast. China, Thailand and Japan, among others, all have extensive train and bus infrastructure; once you’re off the boat or plane, you have free reign of the land with your two feet and the nearest public transportation.

America is different. “It’s three miles to Jo Jo’s,” my brother told me, referring to the nearest convenience store. So the next afternoon I walked it just to see — three miles really isn’t that far. If you want to get to Concord or Manchester or Boston (and beyond), you have to walk a ways farther — more than 10 miles — to catch the Concord Coach bus.

No, I don’t have any urge to get a car for now; I’m resigned to perambulate until I feel fatigue or frustration. Just the other day, after getting dropped at the Moultonborough Public Library (open Mon.-Thurs., 10 to 8)–a fine, modern two-story building with 10 computer terminals, an adequate book and periodical collection and a friendly staff (I got my library card) — I stopped by the local bank for a public notary, ate lunch at a small diner, then walked back toward the eight-mile road home.

Clear skies and temperatures in the 50s made for fine walking, but eventually I decided to stick out my thumb, mostly just to see if I could get a ride. (The last time I hitchhiked was more than 10 years ago, when I lived in the Colorado Rockies).

Two cars passed, then three more. I walked, then turned to face the cars with my right hand extended, thumb out, slowly walking backward. Seven more cars passed, a few at a time. Finally, 45 minutes later, a maroon Chevy pick-up with a large dent in its front right fender slowed and pulled to the edge of the road ahead. I ran up, plopped my bag in the bed and opened the door.

“Thanks for stopping,” I said to the driver, a middle-aged man in a baseball cap and canvas jacket, gray hair pushed behind his ears. “No problem,” he said, as I closed the door. I noticed an Irish terrier sniffing at my head from the crew cab in back.

“Nobody hitchhikes anymore,” he said, pulling the truck back onto the road. “That’s probably why no one stopped,” I said with a chuckle.

“That’s Daisy,” he said, nodding to the friendly dog at my ear. The driver’s name was David. He said he was a builder, used to be a high school science teacher, and had gone through a divorce. He regretted not going back to teaching.

Though I was headed a ways farther past his turn, he insisted on driving me the full distance. “It’s no big deal,” he said. “Plenty of time.”

“That’s it up on the right,” I said as we neared the driveway. Pulling the beat-up truck to a stop on the dirt road, David turned, held out his hand and said, “Good luck with everything.” Again, I thanked him, gave Daisy a pat on the head, stepped down from the truck and started up the driveway toward my new home with the realization that wherever you go in the world, it’s always nice to feel like you’re supposed to be there. Whether in a city or the woods, West or East, we all have someplace to be. You’ll know it when you arrive.

A version of this article originally appeared in the International Herald Tribune.

Print This Post

Print This Post