By Haerin Shin and Angela Becerra Vidergar

Part II

Part I can be read here.

Introduction

This interview was originally part of the previous article on “Terminal Identity and the Contemporary Lifestyle,” but since here Scott, Angela and I focus more on the medium of comics rather than the genre of science fiction, we decided to present this as a separate installment. The following conversation covers a wide range of issues surrounding the creation, consumption, reception of and response to various works of comics mainly within the sphere of American cultures, but one may easily extend the discussion towards a more general discourse on comics across cultural boundaries or linguistic barriers. To provide some context; Angela and I have been leading an academic workshop on comics called “The Graphic Narrative Project.” Our main objective was to create a venue where artists, scholars and consumers come together to investigate and appreciate the unique synergy produced in the combination of graphics and text under an academic light.

ABV: But let’s talk about comics then. What is it about comics that do it for you, and are increasingly doing it for a lot more people? The resurgence of comics commercially, in pop culture, and also in academics. Why do you see this resurgence happening and do you feel that it has something to do with cognition or experience of the world or some particular way in which people are processing things that makes them more amenable to that type of media?

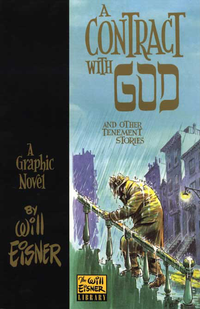

SB: That would be nice if it were true. And it might be true. It’s a good theory — I’ve heard it before, and there is something worthy about it. But I’m somebody who has read comics since I was eleven, so for me it’s not a resurgence; they never went away. But now I can assign them. For me, comics have never been “the form that’s appropriate to the world now,” because they’ve always been appropriate to my world. That’s just the way of it. So: Why has there been the resurgence or insurgence of comics? Film has played no small part in this. I suspect that superhero films had a lot to do with the resurgence and popularity of comics, although I think that superhero films are really a function of technology, specifically CGI. Until the ability to use CGI smoothly, you could not really do a Spider-Man, or a Fantastic Four (well, they still haven’t really done a good Fantastic Four). They couldn’t really do flaming people and stretchy guys…the kinds of things a superhero body could do on paper. Anyway, I think the superhero film is connected to the new visibility of comics, even though superhero comics actually don’t sell that well. At the same time, of course, there has been a big explosion of alternative kinds of comics or, ahem, “graphic novels.”

SB: That would be nice if it were true. And it might be true. It’s a good theory — I’ve heard it before, and there is something worthy about it. But I’m somebody who has read comics since I was eleven, so for me it’s not a resurgence; they never went away. But now I can assign them. For me, comics have never been “the form that’s appropriate to the world now,” because they’ve always been appropriate to my world. That’s just the way of it. So: Why has there been the resurgence or insurgence of comics? Film has played no small part in this. I suspect that superhero films had a lot to do with the resurgence and popularity of comics, although I think that superhero films are really a function of technology, specifically CGI. Until the ability to use CGI smoothly, you could not really do a Spider-Man, or a Fantastic Four (well, they still haven’t really done a good Fantastic Four). They couldn’t really do flaming people and stretchy guys…the kinds of things a superhero body could do on paper. Anyway, I think the superhero film is connected to the new visibility of comics, even though superhero comics actually don’t sell that well. At the same time, of course, there has been a big explosion of alternative kinds of comics or, ahem, “graphic novels.”

ABV: One of the things to consider is whether it has to do with readership and how people read today, and whether they read today. This so-called resurgence might correspond also to the so-called crisis in book publishing and the reading of books. I wonder whether that has any correlation. If people are more willing to read graphic novels, or more interested or intrigued by them…

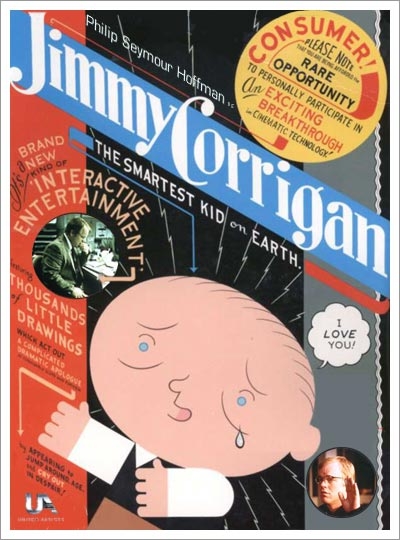

SB: But there are some assumptions there. First, that someone who is buying a graphic novel is someone who doesn’t buy a novel. That if they are reading graphic novels, they are not reading regular novels. I wouldn’t be a bit surprised to find that a lot of people are like me: they’re reading prose and they’re reading comics. They are book buyers. And they are book buyers regardless of what aisle the book is in. I don’t know that that is true, but I’m challenging the assumption that there has been a shift from this set of people who buy books to this set of people who now buy comics. I imagine there is cross-pollination there. I do think there are probably people who buy graphic novels, and there are people who illegally download graphic novels. There are people who buy books and there are people who pirate  books. I think there are readers who are still invested in the book as an object and for whom the prettiness of a Chris Ware book or a Dan Clowes book…the beauty of these as objects is just really seductive. They’re nice to have, they’re nice to hold and they really are keeping a very good idea alive — that the book is an object, a material form. But I don’t know whether a new population of readers has arisen for whom graphic novels are their chosen medium. I just don’t think that’s true. I do know that I am less and less embarrassed to bring out a comic book on an airplane. I used to bring out the latest Ed Brubaker Captain America collection, and then just to make sure the person next to me knew I just wasn’t completely retarded I would bring out Sartre’s Being and Nothingness and put that down there, too, so that way maybe I’d have some credibility. I no longer feel as worried about that. But I was still on a plane the other day and I was reading Dash Shaw’s BodyWorld and the guy next to me said, “So, what is that you have there?” I handed it to him, he looked at it, gave it back and said, “So it’s like a big comic book.” I thought, “Where has this guy been?” I’m walking around assuming that every human in the world knows that comics have arrived, and yet I don’t see that many people on airplanes or on the beach reading graphic novels or comics. I see them reading paperbacks and magazines. So I’m not sure how big the penetration has been in the general population so far, when I still have to explain what a graphic novel is to someone. So, I’m not sure about some of the assumptions that are going on here. I do think that comics are awesome in all their manifestations, however. [added 2012: Including on my iPad.]

books. I think there are readers who are still invested in the book as an object and for whom the prettiness of a Chris Ware book or a Dan Clowes book…the beauty of these as objects is just really seductive. They’re nice to have, they’re nice to hold and they really are keeping a very good idea alive — that the book is an object, a material form. But I don’t know whether a new population of readers has arisen for whom graphic novels are their chosen medium. I just don’t think that’s true. I do know that I am less and less embarrassed to bring out a comic book on an airplane. I used to bring out the latest Ed Brubaker Captain America collection, and then just to make sure the person next to me knew I just wasn’t completely retarded I would bring out Sartre’s Being and Nothingness and put that down there, too, so that way maybe I’d have some credibility. I no longer feel as worried about that. But I was still on a plane the other day and I was reading Dash Shaw’s BodyWorld and the guy next to me said, “So, what is that you have there?” I handed it to him, he looked at it, gave it back and said, “So it’s like a big comic book.” I thought, “Where has this guy been?” I’m walking around assuming that every human in the world knows that comics have arrived, and yet I don’t see that many people on airplanes or on the beach reading graphic novels or comics. I see them reading paperbacks and magazines. So I’m not sure how big the penetration has been in the general population so far, when I still have to explain what a graphic novel is to someone. So, I’m not sure about some of the assumptions that are going on here. I do think that comics are awesome in all their manifestations, however. [added 2012: Including on my iPad.]

HS: In that sense I think accessibility is something else to consider. We’ve mentioned the “so-called” resurgence of comics, but I do see a lot of that going on in the academic sphere and the artistic sphere, whereas the accessibility of comics as a medium appears to be growing as it becomes an accepted, or a possible form of high art like in the works we’ve discussed, such as Watchmen or some of the more experimental or conceptually “deep” works that are “worthy” of academic observation. When people who have a conventional notion of comics assess them, they have a hard time; they are actually repelled by the experimental or complicated form and content.

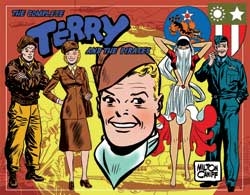

SB: There are a lot of things going on there which I can’t really separate out. One thing I can say is that there has never been a better time in the history of the planet to like comics. There’s more good stuff coming out right now than there has ever been. It’s coming out of the mainstream publishers of comics, it’s coming out of the mainstream book publishers, it’s  coming out of these reprint projects (I can now buy all of Terry and the Pirates in five gorgeous volumes that happily take up space on my bookshelf). I can’t keep up despite my generous funding here at Stanford — I just can’t keep up with all the material that comes out every week. How many great TV shows are showing up every year now? How many great films are coming out every year? There are some, but you have to look really hard to find them. With comics, on the other hand, you’re tripping over great works every week. It’s unbelievable. So when you ask me about the resurgence of interest in it, I think that for some reason there has been an enormous amount of interest in comics, and people are making great comics, and people are publishing that good work. Again, new stuff, old stuff… If you’re a comics historian, there’s never been a better time. I don’t have to go to an archive in the Midwest to look at these things, I have them on my shelf. There has been an unbelievable shift in comics’ accessibility. There’s a comic book out there for everyone — there’s a comic out there for you, for me, and my mother in-law. I love finding the right comic to give to someone for their birthday, because I can always find one. It’s out there. At the same time I think that comics do a lot of different things. And one of the things that we want to say is that reading something like Watchmen is a challenging read. It has all of

coming out of these reprint projects (I can now buy all of Terry and the Pirates in five gorgeous volumes that happily take up space on my bookshelf). I can’t keep up despite my generous funding here at Stanford — I just can’t keep up with all the material that comes out every week. How many great TV shows are showing up every year now? How many great films are coming out every year? There are some, but you have to look really hard to find them. With comics, on the other hand, you’re tripping over great works every week. It’s unbelievable. So when you ask me about the resurgence of interest in it, I think that for some reason there has been an enormous amount of interest in comics, and people are making great comics, and people are publishing that good work. Again, new stuff, old stuff… If you’re a comics historian, there’s never been a better time. I don’t have to go to an archive in the Midwest to look at these things, I have them on my shelf. There has been an unbelievable shift in comics’ accessibility. There’s a comic book out there for everyone — there’s a comic out there for you, for me, and my mother in-law. I love finding the right comic to give to someone for their birthday, because I can always find one. It’s out there. At the same time I think that comics do a lot of different things. And one of the things that we want to say is that reading something like Watchmen is a challenging read. It has all of  these many complicated ways in which text and images relate to each other and the symmetry and structure… but on another layer, comics are just easy things to read. Comics go down smooth.. Nothing makes me happier than when a new edition of Dark Horse’s reprinting of Little Lulu comes out. Little Lulu is not a hard thing to read but it gives me a lot of pleasure, and it’s the pleasure of a well told story where the images are the right images for that text and the stories are inventive variations on a few formulas. For me it’s not about elevating those comics that are hard to read to see them as literature and not taking up comics that are fun and easy to read. I think the pleasures of Watchmen and the pleasures of Little Lulu are not such different pleasures. They’re all comics. I think both of those are part of the beauty of the form. You say Watchmen is challenging — what about something like Brian Chippendale’s Maggots or Ninja? These are comics, too! Watchmen is a walk in the park compared to those.

these many complicated ways in which text and images relate to each other and the symmetry and structure… but on another layer, comics are just easy things to read. Comics go down smooth.. Nothing makes me happier than when a new edition of Dark Horse’s reprinting of Little Lulu comes out. Little Lulu is not a hard thing to read but it gives me a lot of pleasure, and it’s the pleasure of a well told story where the images are the right images for that text and the stories are inventive variations on a few formulas. For me it’s not about elevating those comics that are hard to read to see them as literature and not taking up comics that are fun and easy to read. I think the pleasures of Watchmen and the pleasures of Little Lulu are not such different pleasures. They’re all comics. I think both of those are part of the beauty of the form. You say Watchmen is challenging — what about something like Brian Chippendale’s Maggots or Ninja? These are comics, too! Watchmen is a walk in the park compared to those.

ABV: Or Chris Ware even. The density of it.

SB: Yes, the density of it! Do comics even have to be narrative? English departments are so busy trying to claim them as literature that they’re ignoring the developing area of abstract comics. My friend Andrei Molotiu has edited a book called Abstract Comics, which raises a host of questions: What has to be there for it to  be a comic? Does it have to have sequence? Is the grid necessary? What elements of comics are irreducible? I like these fringe areas, but I also still like Little Lulu. I like it all.

be a comic? Does it have to have sequence? Is the grid necessary? What elements of comics are irreducible? I like these fringe areas, but I also still like Little Lulu. I like it all.

Let me talk about my comics class for a second. My class is called American Comics: History, Theory, Spandex. I decided that in this age where our English departments are happy teaching comics under the rubric of the graphic novel, that I wanted to embrace the range of things that appear under the name of comics. The reason I restricted it to America was simply to have some restriction to the amount of material; the course is only ten weeks long — even with just American comics I can barely scratch the surface. We just finished two weeks on superhero comics. Most academic courses on “graphic novels” avoid the superhero. They’ll do Watchmen, but they won’t treat it as a work of superhero fiction, they’ll treat it as a work of fiction that is critical of superheroes. But they won’t do superheroes. Yet superhero comics have a rich history, and there’s a lot of range within the world of superhero comics. There’s a lot of drivel being produced and there’s a lot of great work being produced and I didn’t want to shy away from it. Anyway, in my course I included comic strips, gag panels, underground comics, kids comics, autobiography, non-fiction, superhero books, then and now, all the way up to abstract comics. If it’s comics, I wanted to fit it into the course somehow. And I really like doing that, and it’s been a lot of fun. But it is a different away to approach the subject. People want to adopt one part of comics but not the other, whereas I find them all equally… (pause) I don’t know why it is that I read someone’s diary comic strip. I don’t want to read the guy’s diary, but I will read his diary strip. What is it about the comics medium that makes me want to read it? I like the form. I like the combination of picture and word or picture and picture. I like the way in which it’s like somebody’s handwriting. In this age where it takes billions of people to make a movie, I like the sense that there is still something “handmade” about a comic. Less and less all the time, but there’s still something handmade about it. I like holding it in my hand, the feel of the paper, I like the smell of the ink. I like the physicality of the form. I really like the density of it but I also like the way it leads me along and I can just read it and it reads to me. It seems to be a very flexible and very supple form, and I worry that the academy actually doesn’t embrace its flexibility, it just skims the cream off the top of a certain kind of comic that gets privileged in that way. And it’s good stuff that gets privileged, it deserves to be examined, it’s just not the whole story.

ABV: I think that ends up coming down to, in part, the separation, especially in the academy, between high culture and popular culture, and high literature and popular literature. This is something that science fiction had to deal with. Like with New Wave SF where authors started trying to be more literary in SF. But comics have to deal with a similar thing today, and with people seeing comics as a genre, rather than seeing that there are different genres within the medium. It seems that that might be part of the reason that superhero comics, for example, are being more or less ignored by people who are trying to bring comics, graphic novels, graphic narratives, or whatever the designation, into classrooms. Both at the primary/high school level and at the college level. Do you see comics as having the potential to successfully break down some of these barriers between high and pop culture?

SB: This is a very, very, very good question. Bear in mind that I’m sitting here in my office at the Art History department at Stanford, and that I was brought in here not to do comics but to do Film Studies. Film had to break down that high-low barrier, because once upon a time the study of film in the academy would have been the study of European film, which was known as art cinema, or the study of the avant garde. Maybe they could have gotten away with Hitchcock. But increasingly it becomes obvious that what we study in Film Studies is the medium of film. There is interesting stuff being produced in Hollywood, then and now, and there are things that need to be discussed. You’re not claiming a film is a masterpiece just because you put it on your syllabus. It’s interesting enough to put on your syllabus because there is something there that we need to talk about. Maybe it’s ideology, maybe it’s the technology. But It doesn’t have to be an imprimatur of quality. In comics it’s the same thing. I think in a way, comics studies is following film studies more than it is following the study of literature. That’s why teaching it in the context of media studies, which is what I do, seems like a fine idea. That said, I have to say that I tend to increasingly only teach things that I really like. So if I put a film on the syllabus, it’s because I do think it is really good. If I put a comic on my list it’s because I think it’s really worth reading. Maybe some of the Golden Age superhero stuff I just put there because it’s the first Superman comic and you should read it. But I think Superman is cool. There is quality there. It’s Superman, for crying out loud! The high-low split is simply an immaterial distinction, because while I like things that are popular, I don’t like them because they’re popular, I teach them because I have something to say about them. Sometimes people describe me as someone who teaches popular culture, but what I should probably say is, “No, I teach Scott culture.” I teach things that I like, and that’s why I teach them. Sometimes they’re popular and sometimes they’re not — it’s the luck of the draw. And in my comics class I’m trying to get across a sense of the complexity of the medium by teaching as many aspects of it as possible so they don’t think that they know what comics are by having read Nancy or that they know what comics are by having read

Watchmen. No, no no. It’s all these things. It’s the safety card in the seatback of an airplane that shows you how to use your seat cushion as a flotation device. Comics are everywhere, and I want my students to recognize how much is out there. I never ever think about these things in terms of popular culture because I am the guy that sat there on the weekend Titanic opened, saying to myself as the film ended, “Nobody is going to like this piece of shit.” I have no idea what makes something popular and I have no idea why the thing that I love most nobody else in the world likes. I can only talk about what I find interesting about something. That is what my career has come down to at the moment. It’s sort of explicating my attraction to something in terms that make sense to someone else. So that it isn’t just navel-gazing — “Here’s Scott’s comic collection, write a paper about it and you get credit.” It’s not about that. But rather, being able to explicate the fascination in a way that makes sense to someone else and have them think, “Yeah, that is fascinating. Maybe Little Lulu is cool.”

Watchmen. No, no no. It’s all these things. It’s the safety card in the seatback of an airplane that shows you how to use your seat cushion as a flotation device. Comics are everywhere, and I want my students to recognize how much is out there. I never ever think about these things in terms of popular culture because I am the guy that sat there on the weekend Titanic opened, saying to myself as the film ended, “Nobody is going to like this piece of shit.” I have no idea what makes something popular and I have no idea why the thing that I love most nobody else in the world likes. I can only talk about what I find interesting about something. That is what my career has come down to at the moment. It’s sort of explicating my attraction to something in terms that make sense to someone else. So that it isn’t just navel-gazing — “Here’s Scott’s comic collection, write a paper about it and you get credit.” It’s not about that. But rather, being able to explicate the fascination in a way that makes sense to someone else and have them think, “Yeah, that is fascinating. Maybe Little Lulu is cool.”

ABV: That is a really interesting way to approach teaching and education. I think it’s possible it may more accurately affect the way that people consume works of art and culture. People go for the things they like, in general. That sometimes is the gap between the academy and the general public — this gap between what is valued and what is actually consumed and liked…

SB: What you actually put on the TV or download when you go home after teaching your literature seminar…

ABV: What stories we are drawn to.

SB: What are you actually watching and why aren’t you talking about it? Why not talk about The Real Housewives of New Jersey? It is no secret that Film Studies and the academy in general were very suspicious of pleasure for about a decade and a half. If you were attracted to something then it was thought that there was some need to try to get some critical distance on it, in order to understand the ideological operation that you were being seduced by. I got tired of that real fast. When I was writing my dissertation I wrote an analysis of Blade Runner that was a really good analysis of Blade Runner. It was about commodification and dystopia and well… I don’t remember what it was about, but it was good. And I read it, reread it, went over it again and I thought: this has nothing to do with why I like Blade Runner. I mean, first of all, I liked Blade Runner. But if you’d read this, you wouldn’t have known. It didn’t account for what I liked about the film at all, and I had to go back and think of another approach, which was more phenomenological: the way the camera moved through space, the way light worked, the way color worked, the sensuality of the film, the things that kept me coming back to it. Not the ideological valence of the idea of the replicant as a commercial product… that’s there too, but that’s not why I liked it, that was something else. I was speaking for some hypothetical me, and that didn’t work. That’s when I made a switch and realized that I needed to account for my own pleasure in the object if I’m going to get at it at all. Blade Runner is a film about a dystopian future but it is not a dystopian film. It’s built around a utopia of vision. Cameras penetrate space, machines explore the hidden recesses in a photograph, things like that. Then it complicates the act of vision by taking place in a world where vision can’t tell you whether you are talking to a human or a replicant. But the pleasure of vision is why you want to watch the film again and again, even when you know the story. You’re not going to see the story again, you’re going to watch the camera move. You’re going to look.

HS: That is fascinating. Academia would be heaven if it everyone had that perspective, and had fun.

SB: Well that’s what I try to do. That’s the job as I see it.

ABV: Everyone talks right now about a crisis of the humanities, and people not signing up for humanities courses. I think a lot of that has to do with the loss of that pleasure of these art objects.

SB: That’s right. You’re not allowed to love it. You major in a subject in order to “master” it. What kind of word is that? “I am its master.” I want it to be my master, let it master me! A great rejoinder to Laura Mulvey’s analysis of the gendered, sadistic, male gaze, was an essay by Gaylyn Studlar, “Masochism and the Perverse Pleasure of the Cinema,” where she concentrated on the masochistic position of the spectator at the cinema — we don’t watch film in order to wield the gaze of mastery; we surrender to the film. We give ourselves over to it, and it takes control of us. And that, to me, is a much more compelling model of how a text works on me.

HS: It is interesting that you are “allowing.” Everyone has different feelings toward a certain film or media so actually you still have the control within…

SB: You have choice. What film do I want to surrender to and what film do I not want to surrender to?

HS: Whether I like it or not like it, how do I like it… which aspects?

These are very personal feelings you hold towards these films or comic books. How do you convey your feelings in a classroom setting?

SB: I just try to be articulate about it. In today’s class I spent a lot of time on Grant Morrison’s All-Star Superman and also some other Grant Morrison comics, and I said, “I find Grant Morrison to be a fascinating figure, here’s why.” Then I tried to demons trate and illustrate it. They seemed to get it, I think I sold a couple people on it. Luckily they liked All-Star Superman, and that was half the battle. You can’t go in as a fan, and say “I like this, the end.” It’s not about me in any way, shape, or form, but the starting point is always my fascination with a thing. Then I put that fascination into a broader context that makes sense to other people. But the starting point is me — not some fictional “subject.”

trate and illustrate it. They seemed to get it, I think I sold a couple people on it. Luckily they liked All-Star Superman, and that was half the battle. You can’t go in as a fan, and say “I like this, the end.” It’s not about me in any way, shape, or form, but the starting point is always my fascination with a thing. Then I put that fascination into a broader context that makes sense to other people. But the starting point is me — not some fictional “subject.”

HS: Would you define the role of somebody who is studying, not just enjoying comics as a medium, as to go over these three layers, just liking as an initial point, but then being able to explain and then be able to find meaning beyond explanation?

SB: I’m a little allergic to the word meaning, because I’m not very meaning-driven, but I would say that you begin with a response, and you want to figure out what has engendered that response. You want to be learned enough that you have some method of doing so. To understand, for example, that the instability of identity is an important idea. You’re encountering it in a Superman comic but it has larger implications, and you’re aware of that because you also read real books. You’re able to place those tropes in a broader context and reflect upon your relationship to it. It’s a bit of a back and forth between the bookshelf and your response, Trying not to take the theory bookshelf and just map it onto your Superman comic but rather see what the Superman comic does to the theory bookshelf — how does a Superman comic add to our understanding of the multiplicity of identity and the appeal or fear of that? Maybe the thing we get at is not meaning at all but an understanding of your response. Understanding.

HS: Do we have to define meaning?

SB: No, I have no clue what anything “means.” I can barely follow a story. I never know who done it. I’m not a story guy, I’m a camera movement guy, I’m a performance guy… a pictures on a page guy. I like the way things look, or the way things act… the momentary pleasure. Is the pleasure in the narrative watching how the narrative resolves (making the ending the most important thing there) or is the ending just a way to get out of the narrative because it’s been 90 minutes or 300 pages or whatever, and what you’re really doing is enjoying it all the way along because it puts these people in contact with each other and they talk and have a scene and that’s cool to see, and then they get in a car and chase each other, and chasing each other is good, we like that, that’s exciting. And how it ends… maybe that’s just not all that important after all. When you go into a James Bond movie, you pretty much know that James Bond is going to win, so you’re not there for that, you’re there for all this other stuff. I like talking about just that, the other stuff.

HS: This brings us back to the initial idea that you’re not really worried about what effect technology is having. People are okay with just knowing that they are there and comfortable with it because as long as you know that something is beyond the screen, you know the fact that they are there, you really don’t have to know all the details or what they mean or how they work. Would that be a more positive or optimistic view?

SB: I see what you’ve done there and it’s very good. But I wonder whether if the stuff I was saying at the beginning of this interview isn’t just the voice of complacency. Everything else I’ve been saying now is not about complacency. It’s about a real, active engagement. Whereas I think we are a bit complacent in our engagement with technology. But we’re complacent in part because computers did not take over the world, we haven’t stopped reading, movies did not make us illiterate.

ABV: It seems it reflects what usually happens with technology. It’s not that we are complacent about technology completely. It’s just that some things have already been around, and we’re not complacent about other things now. Like cloning. People still talk about cloning, people are still interested in it. There are new things we are worried about…

SB: Yes. We’re still worried about cloning, yes. But I do think that it’s not good to be complacent about older technologies. We don’t think enough about cars, perhaps. Well, we should think about our cars! Or the fact that everything is paved, and we all have individual cars, which is kind of silly. We should be thinking about that, but we don’t. We get comfortable and then a new technology worries us, and we worry about that for a little while until we realize… “I can clone myself? Cool!” Then we’re not worried about it anymore.

Print This Post

Print This Post

***********************************

Scott Bukatman is a Professor in the Film and Media Studies Program in the Department of Art and Art History at Stanford University. He holds a Ph.D. in Cinema Studies from New York University and is the author of four books: Terminal Identity: The Virtual Subject in Postmodern Science Fiction, published by Duke University Press, one of the earliest book-length studies of cyberculture; a monograph on Blade Runner commissioned by the British Film Institute; a collection of essays, Matters of Gravity: Special Effects and Supermen in the 20th Century, and most recently, The Poetics of Slumberland: Animated Spirits and the Animating Spirit. His writing highlights the ways in which popular media (film, comics) and genres (science fiction, musicals, superhero narratives) mediate between new technologies and human perceptual and bodily experience.

Scott Bukatman is a Professor in the Film and Media Studies Program in the Department of Art and Art History at Stanford University. He holds a Ph.D. in Cinema Studies from New York University and is the author of four books: Terminal Identity: The Virtual Subject in Postmodern Science Fiction, published by Duke University Press, one of the earliest book-length studies of cyberculture; a monograph on Blade Runner commissioned by the British Film Institute; a collection of essays, Matters of Gravity: Special Effects and Supermen in the 20th Century, and most recently, The Poetics of Slumberland: Animated Spirits and the Animating Spirit. His writing highlights the ways in which popular media (film, comics) and genres (science fiction, musicals, superhero narratives) mediate between new technologies and human perceptual and bodily experience.

Haerin Shin and Angela Becerra Vidergar are Ph.D. Candidates in the Comparative Literature Department at Stanford University.

Haerin writes about fictional depictions of alternative modes of the human mind and existence, topics ranging from tales of the supernatural and horror, digital media and cybernetic bodies, ontological veins of philosophy and critical theory, and psychoanalysis in literary criticism.

Haerin writes about fictional depictions of alternative modes of the human mind and existence, topics ranging from tales of the supernatural and horror, digital media and cybernetic bodies, ontological veins of philosophy and critical theory, and psychoanalysis in literary criticism.

***

Angela is a literary and cultural scholar primarily focusing on the way we imagine and envision the future, particularly in terms of our relationships to technology, progress, the violence of the past century and the resulting cultural obsession with fictionalizing disaster and apocalypse.

Angela is a literary and cultural scholar primarily focusing on the way we imagine and envision the future, particularly in terms of our relationships to technology, progress, the violence of the past century and the resulting cultural obsession with fictionalizing disaster and apocalypse.