By Sam Sheppard

To say it’s been a high-profile time here in Korea would be an understatement. As anyone with access to some form of media outlet will attest, news of rekindled animosity between the Northern and Southern halves of the peninsula has dominated the headlines.  Since the November 23rd shelling of Yeonpyeong Island, in which at least four people are confirmed to have died, the various regional players have each traded statements, with the South, North, and China, issuing cries of outrage, defiance, and caution respectively. The political web underwriting any such interactions is so complicated and positions so deeply entrenched that the debate will surely rumble on for some time. Yet, within a few days, the South’s Defence Minister Kim Tae-young’s ‘muted’ response to Pyongyang’s actions had been denigrated to such an extent that it forced his resignation.

Since the November 23rd shelling of Yeonpyeong Island, in which at least four people are confirmed to have died, the various regional players have each traded statements, with the South, North, and China, issuing cries of outrage, defiance, and caution respectively. The political web underwriting any such interactions is so complicated and positions so deeply entrenched that the debate will surely rumble on for some time. Yet, within a few days, the South’s Defence Minister Kim Tae-young’s ‘muted’ response to Pyongyang’s actions had been denigrated to such an extent that it forced his resignation.

Such drastic action was certainly in line with the views of my students, who have reveled in threatening the lives of not only Kim Jong-il, but also his father, the long-deceased founder of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Kim Il-sung. Taking their gung-ho enthusiasm with a pinch of salt, I’ve still yet to draw any meaningful thoughts on the incident from my fellow members of staff, despite the issue being the de facto conversational opener. Whilst I am asked on a daily basis whether, given the danger, my family will insist that I return home, no one has offered their fears or insecurities to me in any significant way. Perhaps this stems from pride and a desire to maintain the confident, progressive face South Korea has presented to the world for decades now, or perhaps it’s attributable to geography once again, and the fact that Busan sits some 350km and 28,000  US troops from the border.

US troops from the border.

As such, the only criticism I’ve been privy to since the shelling has centered specifically on President Lee Myung-bak, rather than any of the global superpowers with vested interests in the divide, or even the ideological polarity to the North. Late last week, one of the teachers at my school told me that, under normal circumstances, she wouldn’t be too concerned about the North’s cage-rattling. However, given the current President, she was nervous regarding the South’s response. Mr Lee was, in her words, one of ‘God’s sons’—that elite group of affluent Koreans sheltered by their wealth, immune to the tribulations undergone by the people during the latter half of the 20th century. In simple terms, she worried that his lack of military service left him ill-equipped to deal with the potential escalation of tensions along the 38th parallel.

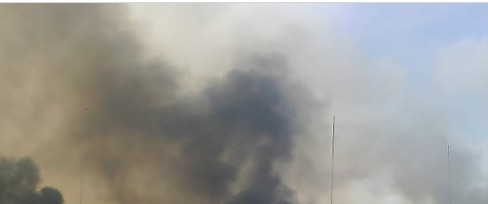

For the past several days, whenever I’ve looked online for news of border relations, I’ve been greeted with some quite harrowing images. From civilians and marines initially evacuating the island, to the distraught relatives of the fallen and even protesters burning depictions of the North Korean hierarchy, the panic and animosity has seemed substantial. Yet, in this time which has seen shells fired and lives lost, the only ill-feeling aired directly to me has been a logical and considered noting of the President’s relative inexperience. For a country on the brink of large-scale conflict, as various news agencies would have you believe, this seems remarkably subdued.

Taking a trip to Gyeongju over the weekend, the tranquility found amidst the gently rolling hills was also at odds with the furor reported by the media. As befitted the ancient capital of the Shilla Kingdom, I spent my afternoon navigating burial tombs and watchtowers, breathing in the country air and attempting to clear my head after an incident-packed week. Any sense of conflict or tension was non-existent. In fact, I’d say it was the most placid day I’ve spent in Korea so far. Renting a bicycle for several hours ensured only the sound of the wind accompanied my wandering, while the general lack of busy streets—presumably given the time of year—lent the whole experience a tangible air of serenity. In addition, building restrictions placed on the city ensure that no towering skyscrapers have inched their way up over the last 30 years, so it felt a little like stepping back in time, away from the rampant, neon-lit capitalism that both defines modern Korean society, and so irks its closest neighbour.

the gently rolling hills was also at odds with the furor reported by the media. As befitted the ancient capital of the Shilla Kingdom, I spent my afternoon navigating burial tombs and watchtowers, breathing in the country air and attempting to clear my head after an incident-packed week. Any sense of conflict or tension was non-existent. In fact, I’d say it was the most placid day I’ve spent in Korea so far. Renting a bicycle for several hours ensured only the sound of the wind accompanied my wandering, while the general lack of busy streets—presumably given the time of year—lent the whole experience a tangible air of serenity. In addition, building restrictions placed on the city ensure that no towering skyscrapers have inched their way up over the last 30 years, so it felt a little like stepping back in time, away from the rampant, neon-lit capitalism that both defines modern Korean society, and so irks its closest neighbour.

Feeling somewhat refreshed, I boarded the bus back to Busan as the sun set. As I slipped into my expansive seat, I was anticipating little more than an hour’s sleep, along with a few helpings of the Gyeongju bread I’d bought earlier in the day. Soon, however, the neon hue returned in earnest along with the gentle buzzing of the TV. Tuned to a Korean news channel throughout the journey, passengers were shown scenes of the naval maneuvers being jointly performed by US and Southern troops in the heart of the Yellow sea. Despite my lack of comprehension, it slowly dawned on me that tensions were still high, that no resolution had yet been agreed and that, crucially, many were increasingly baying for blood.

This issue had raised its head a few days before, during the judging of my school’s English speaking contest. Amidst the saccharine speeches on family, friends and the like, one sixth grade student stood out. He was no more articulate or well-versed than the others, but, for around two minutes at least, he turned his thoughts to an altogether more macabre topic. Of course, given the polished hand gestures and bubblegum tone, I found it  difficult to tell exactly how impassioned his plea for Korean unification really was. He spoke of the families temporarily reunited on the slopes of Mount Geumgang, of siblings harbouring half century uncertainties as to one another’s fate, and of the promise from one man that he would live to 100 in order to see his children again.

difficult to tell exactly how impassioned his plea for Korean unification really was. He spoke of the families temporarily reunited on the slopes of Mount Geumgang, of siblings harbouring half century uncertainties as to one another’s fate, and of the promise from one man that he would live to 100 in order to see his children again.

Sandwiched between talks on fireworks and soccer, it felt curiously out of place, almost running counter to the rows of expectant parents and assiduous notes of the judges. His words fell on smiling faces and uncomprehending ears, but also, somewhat strangely, seemed contrary to the sea breeze and light streaming through the windows. In that moment, it was clear that no one spared a thought for the dissection of a people or the question of how best to seek reunification. The ‘Sunshine’ policy of openness towards the North was in scant evidence, just as Lee Myung-bak had wished. Looking around the classroom during the winners’ announcement, parents celebrated with their children whilst teachers encouraged those not so fortunate—all lost in the small victories and minutiae of every day life, a far cry from the trauma and heartache in the news.

Before I came out to Korea I often thought about the instability of the peninsula and what it would be like to live in a country still technically at war. Upon my arrival, my thoughts turned to the more tangible matters of settling into my new job and home. My recent trip to the DMZ was eye-opening, but not exactly the steely wake-up call I’d anticipated. Having lived quite undisturbed through years when the UK was subjected to bombings and repeated threats of violence, it seems short-sighted to focus solely on the potential interruptions to peace, but at the same time they remain a source of fascination. In any case, I probably needn’t worry. Busan still feels detached from the whole thing sometimes. I, for one, blame the beaches; they make people so level-headed.

______________________________________________________________

Sam Sheppard left London and arrived in Korea just over three months ago. He works in Busan as an elementary school teacher and bores all that will listen with his blog The Illiterati.

Sam Sheppard left London and arrived in Korea just over three months ago. He works in Busan as an elementary school teacher and bores all that will listen with his blog The Illiterati.