By Sam Sheppard

Author’s Note: When I began writing this piece in January, following a ten-day period crisscrossing Japan, it’s no exaggeration to say that the country occupied another place entirely within the popular consciousness. Since then, the sequence of events that began on March 11th when the 9.0 magnitude earthquake struck the Tōhoku region has shifted everything. Japan’s 3/11 as America’s 9/11. No one can ever utter, or shrug the shoulders at the word “Japan” in quite the same way. Nowhere is this truer than in the Republic of Korea. Here, derision has been usurped by sympathy, mild dislike by  overwhelming concern and sadness. When I was putting together the original draft those weeks ago, I had hopes of highlighting some of the inner-workings of Japan, in addition to its unique and fractured place within the minds of Koreans. I felt I experienced a great deal during my time there, but I fear I have been pushed back towards square one by Mother Nature’s untimely intervention.

overwhelming concern and sadness. When I was putting together the original draft those weeks ago, I had hopes of highlighting some of the inner-workings of Japan, in addition to its unique and fractured place within the minds of Koreans. I felt I experienced a great deal during my time there, but I fear I have been pushed back towards square one by Mother Nature’s untimely intervention.

Since the disaster began to unfold, I have felt my knowledge of the island evaporate with increasing fervour, as if I somehow experienced a Japan that no longer exists, although I know how overly dramatic that must sound. It’s infuriating to witness your understanding of something so suddenly displaced by a series of tragic events, so it was with huge excitement that I received the news that Haksung, the husband of one of my co-teachers, was returning from his latest spell at The University of Tokyo, where he is in the final stages of completing a PhD.

Having spent my time during the aftermath watching videos of the Japanese coastline whilst attempting to grasp the extent of the seismic, aquatic, nuclear, and humanitarian implications, I was eager for her to pick his brains and have him describe what it was like to be living in Tokyo during such tempestuous times.

To my delight, my co-teacher invited me to dinner during Haksung’s stay, presenting a wonderful opportunity to discuss the Japanese people’s perspective with him myself. Not only was his English perfect, but he was more than willing to tell tales of the cracks that appeared in the walls of his lecture theatre as the ripples passed through, of the empty convenience store shelves that he was greeted with on his way home that evening, or even of the increasingly complex seismic activity taking place underneath the Kantō plain, which could have a significant impact on Tokyo’s future as a leading global city.

In terms of the day-to-day practicalities of existing within a disaster zone, he said he was lucky, in as much as he was located very centrally within the city, and was therefore able to walk to his halls of residence with minimum fuss. One of his fellow students, who had recently moved to cheaper accommodation on the outskirts, was faced with a four hour trek home. As he put it, the period immediately following the quake was like stepping back in time one hundred years.

I asked Haksung, somewhat predictably, whether his family in Busan had been concerned upon hearing of the earthquake. Of course they had at first, he replied, but a consensus was quickly reached in which the continuation of his studies was prioritised, provided the threat of nuclear fallout continued to recede. He joked that the incident had brought the Korean out of everyone, that the importance of his academic career was only heightened by the series of natural disasters.

Despite their purported dislike of one another and bubbling political tensions, the Korean people seem hugely saddened by the plight of the Japanese and eager to help in any way they can. It’s been bizarre to experience such a philanthropic surge towards the Eastern neighbours, particularly amidst the recent inundation of Dokdo-based propaganda, which has included political slogans printed on bottles of soju, as well as a full-page advertisement taken out in the New York Times explaining the Korean claims to the island in rather moralistic tones.

Prompted by my incessant questioning, Haksung explained to me in detail his view that the whole affair could prove mutually beneficial in the long run. He believed that, by virtue of humanising the Japanese nation to such an extent, the earthquake could lead to closer ties with Korea in the future. As a man who spoke both languages, having studied and worked on either side of the East Sea, I was inclined to believe him and contemplate not only his boundless optimism and drive, but also the formidability of such a partnership rising from the current debris.

In the context of this conversation, it seems immensely difficult to salvage any remnants of authenticity from my earlier time in Japan, but we all have to carry on so…

Part 1

I remember it in the first instance as a phenomenally expensive country, something in stark evidence even from my viewing platform behind the windows of budget motels and modest restaurants, as well as a fact that may well remain unchanged throughout the protracted rebuilding process. Of course, it is not especially different to a city  like London in terms of consumer purchasing power, but I was always led to believe that the Thames Valley was a special case of high pricing, effectively unmatched by anywhere else in the world. I dread to think what Tokyo must be like. I didn’t even make it that far, yet still managed to find all but the most basic amenities out of my price range after a week or so.

like London in terms of consumer purchasing power, but I was always led to believe that the Thames Valley was a special case of high pricing, effectively unmatched by anywhere else in the world. I dread to think what Tokyo must be like. I didn’t even make it that far, yet still managed to find all but the most basic amenities out of my price range after a week or so.

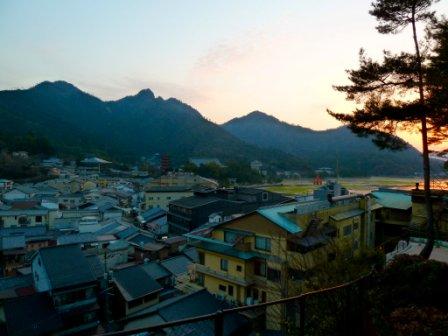

Using my JR Rail Pass to the fullest, I was able to take in Hiroshima, Himeji, Kyoto, Mishima, Osaka, Nara, and Nagoya during my stay, alongside brief stopovers in Fukuoka and Kobe. In hindsight, I was immensely and unknowingly fortunate, as I largely avoided the area directly affected by March’s events, thereby preserving a margin of validity. In this fell swoop, then, I trudged around five more cities than I have in Korea – despite my being here for the last six months – all the time searching for the Japan I’d grown up with. Now, I am fully aware of how pretentious that sounds as a phrase, having absolutely no Japanese ancestry or previous history with the country. However, I should point out that as a younger, marginally nerdier man, Japan was perhaps the one foreign-speaking country that seemed to be on constant display.

Growing up in the company of various home entertainment systems ensured that I spent my days surrounded by stories, characters, voices, and even animation styles, imported directly from the land of the rising sun. As a case in point, when attempting to navigate my way around the Kansai area in central Honshu, I found I recognised  numerous towns and area names on the map. None of these mental associations had anything to do with the geographical locations themselves; rather they were words I recalled seeing colourfully written on TV screens years earlier, when whiling away my Saturdays in the company of Nintendo and Sony’s finest.

numerous towns and area names on the map. None of these mental associations had anything to do with the geographical locations themselves; rather they were words I recalled seeing colourfully written on TV screens years earlier, when whiling away my Saturdays in the company of Nintendo and Sony’s finest.

Mishima stole my attention in the first instance, being the namesake of the central family from the perennial Tekken franchise. My eyes then scanned northwards, before noticing Yokosuka and bringing memories of the ill-fated Shenmue duology flooding back. Days later, when attempting to decide which of Kyoto’s many temples I could cram into my final stint there, I caught sight of Nanzenji temple – the awe-inspiring, zen-infused hub of the Kyoto Basin, as well as the setting of a stream of kabuki plays which, in turn, formed the basis for the Ganbare Goemon (Mystical Ninja) series.

I have no desire to kick a nation while it’s down but, even before the recent devastation, it was inevitable that the eventual realisation of my desire to visit Japan was destined to end in disappointment. From such an idealised and infantile perspective, the reality fell short in ways too innumerable to list here. I commented to my friend at the time that perhaps the whole country would seem far more alien to us if we had traveled directly from the UK to visit. Coming from a base in Korea seemed to anesthetised me to large portions of the Japanese experience, predominantly because I had already seen similar things at work in Korea with equally, if not more, bizarre and disorienting results. In fact, it was precisely this lack of absurdity that was most shocking to me during my time there, and led to the conclusion that Japan is a far more cosy bedfellow of the UK than Korea, despite the tangible air of mystery and intrigue that still surrounds it, as well as the purported hegemony of Starbucks, Dunkin’ Donuts, ESPN, and other facets of ‘Western culture’ in Seoul and Busan.

Clearly, in some highly visible regards, Japan is poles apart from the West. The abundance of temples and shrines I glimpsed during my time there were a beautiful testament to the interweaving pillars of Shinto and Buddhism, sat harmoniously alongside the grandiosity of various city castles, themselves brimming with shogunate opulence. In all honesty, I’ve never felt further from home than the initial moment I set eyes on the Golden Pavilion in Kyoto, with its perfectly reflected mirror image on the water and surrounding gardens frozen with serenity. Yet, within twenty minutes of this unforgettable sight, I was back on the bus again, traveling downtown amidst sensibly dressed office workers, tired but dignified elders, and students respectfully conceding their seats to those more in need. In short, I returned to a better-working model of the UK, largely stripped of the wackiness and delirium I had so hoped to drink in.

Clearly, in some highly visible regards, Japan is poles apart from the West. The abundance of temples and shrines I glimpsed during my time there were a beautiful testament to the interweaving pillars of Shinto and Buddhism, sat harmoniously alongside the grandiosity of various city castles, themselves brimming with shogunate opulence. In all honesty, I’ve never felt further from home than the initial moment I set eyes on the Golden Pavilion in Kyoto, with its perfectly reflected mirror image on the water and surrounding gardens frozen with serenity. Yet, within twenty minutes of this unforgettable sight, I was back on the bus again, traveling downtown amidst sensibly dressed office workers, tired but dignified elders, and students respectfully conceding their seats to those more in need. In short, I returned to a better-working model of the UK, largely stripped of the wackiness and delirium I had so hoped to drink in.

I know how tired and clichéd a sentiment it is to point to Japanese efficiency as a defining characteristic, but it’s hard to think of any other way to summarise the spectacle of Osaka shoppers dividing the covered walkway into twin shifting columns, creating two flows of pedestrian traffic as seamlessly as sand being parted by the oncoming tide. “The nail that sticks out gets hammered in”, so the saying goes, even in a city renowned for the coarse austerity of its citizens. Of course, this points to collective unity as a revered and highly visible aspect of the national psyche, just as I believe it is to some extent with all island nations, but it seemed somehow too flawless, devoid of the fractiousness that makes life in Korea so lively and exciting.

As a Brit, I’m quick to point out our expertise when it comes to the noble art of queuing. Banks being the notable exception, with their carefully ordered, open-plan seating arrangements and metronomic ticketing system, the concept of forming an orderly line based on arrival time when entering, exiting, climbing, descending, sitting, or indeed purchasing, anything in Korea is as alien as facial hair. Personal space and decorum in such situations were one of the first things I learned to abandon upon my arrival in Busan, so it was refreshing to return to a culture in which harmony and the greater good were lionised in a more commercial and pedestrian-friendly fashion. No doubt Koreans are a hugely patriotic and united people, but I felt a great affinity with the way the Japanese smoothly glided through their cities, free of the stray elbows and subway bottlenecks.

of queuing. Banks being the notable exception, with their carefully ordered, open-plan seating arrangements and metronomic ticketing system, the concept of forming an orderly line based on arrival time when entering, exiting, climbing, descending, sitting, or indeed purchasing, anything in Korea is as alien as facial hair. Personal space and decorum in such situations were one of the first things I learned to abandon upon my arrival in Busan, so it was refreshing to return to a culture in which harmony and the greater good were lionised in a more commercial and pedestrian-friendly fashion. No doubt Koreans are a hugely patriotic and united people, but I felt a great affinity with the way the Japanese smoothly glided through their cities, free of the stray elbows and subway bottlenecks.

By not making it quite as far as Tokyo, I was unable to sample the joys of Harajuku on a Sunday, along with its anime-fueled costumes and wild expressionistic license. This in itself may have been the root of my disappointment, as capital cities are usually trendsetters across the board, but I feel I saw enough to judge Japan as an extremely attractive place to live and work, despite subsequent events, yet somehow less captivating than its pugnacious and chaotic counterpart across the sea. In a predictably naive way, I was expecting to glimpse a Korea of the future, a society at a more advanced stage of that shifting process of modernisation to which all ascribe.

The famed Japanese novelist Yukio Mishima once credited “elegance and brutality” as the contradictory, yet defining aspects of his people and culture. As befits a nation that suffered the last of its growing pains over half a century ago, the pacifist constitution of Japan renders the latter half of his sentiment redundant, at least outside the tentacled realms of adult manga. However, a mere cursory glance at the history of feudal Japan and the warring shogunal factions gives a clear indication of this dialectical arrangement.

Korea, by contrast, does not have quite such a crimson and self-mutilating backstory – hinted at by the placidity of temples such as Beomeosa and Haedong Yonggungsa, themselves largely free of the tales of bloodshed and intrigue that accompany so many cultural spots in Japan – yet an evening street scene in any given city will invariably throw up the heady amalgamation of raised voices and jostling, juxtaposed with stilettos and hands covering smiles, all surrounded by a sea of phlegm. Perhaps a fitting aphorism would be in the vein of ‘irritation and fragility’, but this is very much a work in progress.

street scene in any given city will invariably throw up the heady amalgamation of raised voices and jostling, juxtaposed with stilettos and hands covering smiles, all surrounded by a sea of phlegm. Perhaps a fitting aphorism would be in the vein of ‘irritation and fragility’, but this is very much a work in progress.

As a long-established power on the global stage, it should really come as no surprise that Japan has found its level with regards to the international community, subterranean uncertainty aside. Certain imports from abroad are in widespread evidence, such as Marlboro Lights and blonde hair dye, but on the whole it is a nation more than at ease with the twin demands of retaining its own sense of identity whilst simultaneously forming an integral pillar as part of the wider world, striking the balance between globalised and isolated with a sense of the adroit that only comes with advanced levels of development.

Popular music struck me as an especially good example of this, as city centres during my stay were largely free of the Lady Gaga/Katy Perry cocktail that echoes from all corners of Korea. The Japanese seemed divided between their own brand of teddy-boyesque sugar pop, and a bizarre style of freeform jazz, which graced the background of everything from department stores and restaurants, to the weather forecast. On the whole, the usual aural suspects were nowhere to be seen, which made for a refreshing change despite the fact that the vast majority of youths appeared intent on sartorially replicating either Jon Bon Jovi or M.I.A.

If Japan has succeeded in crossing that seemingly treacherous gap of embracing its role as an internationally-minded key economic player, without compromising its diaphanous cultural substance, then it has done so through a combination of collective dedication and pragmatism. Such a stance requires everyone to keep their hearts in the past, but eyes unflinchingly on the future, and will doubtless be exhibited widely during the upcoming months. An export-driven economy has eased friendships and alliances around the world, as well as the assimilation of small pockets of unadulterated Japanese culture, with the appropriate respect garnered from the wider community on account of its dependability and ever-presence.

Korea, for all its faults, retains its unique charm precisely through an inability to sychronise to quite the same extent, with the return leg of my journey a case in point. Taking what could loosely be billed as a cruise from Osaka to Busan, I found myself entertaining such thoughts and smiling throughout – more so, in fact, than I had done at any other point of the trip. The scene could not have been more different to the Japanese preoccupation with the harmonious aesthetic: ajummas jostled for position in the meal queues, hoards of studious teenagers clad in Manchester United sports jackets wrestled with one another, clusters of teenage girls gawped, pointed and laughed at the few Western passengers.

Photo 1 (AP)

All other photos are the author’s

Print This Post

Print This Post

__________________________________________________________

Sam Sheppard left London and arrived in Korea just over three months ago. He works in Busan as an elementary school teacher and bores all that will listen with his blog The Illiterati.

Sam Sheppard left London and arrived in Korea just over three months ago. He works in Busan as an elementary school teacher and bores all that will listen with his blog The Illiterati.